How many photos?

Hunting down numbers shrouded in the mists of time

On being a nerd

A few months ago, I came across a statistic that gave me pause — an impressive insight that begged to be shared:

In 2023 the world generated around 123 zettabytes (that is, 123 trillion gigabytes) of data, according to International Data Corporation, a market-research firm. Picture a tower of dvds growing more than 1km higher every second until, after a year, it reaches more than halfway to Mars.

This is the kind of tidbit that I love to bring up at parties while making a “head exploding” gesture with my hands. This may explain why I haven’t been invited to many parties lately.

More recently, I came across a different claim which seeks to put our obsession with digital and smartphone photography into a historical perspective:

More photographs will be taken this year [2015] than in the entire history of film photography.

I became an avid photographer in the latter part of the 20th century when film photography was extremely popular, and my love of photography has continued through the introduction of digital cameras and smartphones. While I realize that many more photos are taken today than in the past, I found this claim to be astounding because it clearly illustrates the immense scale of the increase.

As I researched further, I found several variants of this claim, like this one from 2023:

More photos were taken in the last two years than in the entire history of photography before that.

And this one:

Every 2 minutes today we snap as many photos as the whole of humanity took in the 1800s.

But wait…all of these statements rely upon being able to estimate how many pictures are taken today and how many pictures were taken on film throughout photography’s history, which extends back to 1822. I can imagine that it would be feasible to make estimates for recent years (more about that later), but where would the data come from to make estimates for the 20th century and even for the 1800s?

This seemed like a simple question, but it wasn’t. For several weeks I have journeyed down a rabbit hole, really more of a rabbit warren. Here’s my report.

One Thousand Memories

As I googled “how many photos were taken in the 20th century”, “how many film photos were taken”, and so forth, I found numerous articles that repeated identical statistics and claims. Moreover, it turned out that those statistics and claims originated from a single source.

That source was an article found on a website called 1000memories.com. I say “found”, but you can’t actually find it anymore. If you try to go to 1000memories.com, your browser, after some ominous warnings about an insecure connection, will take you to this web page:

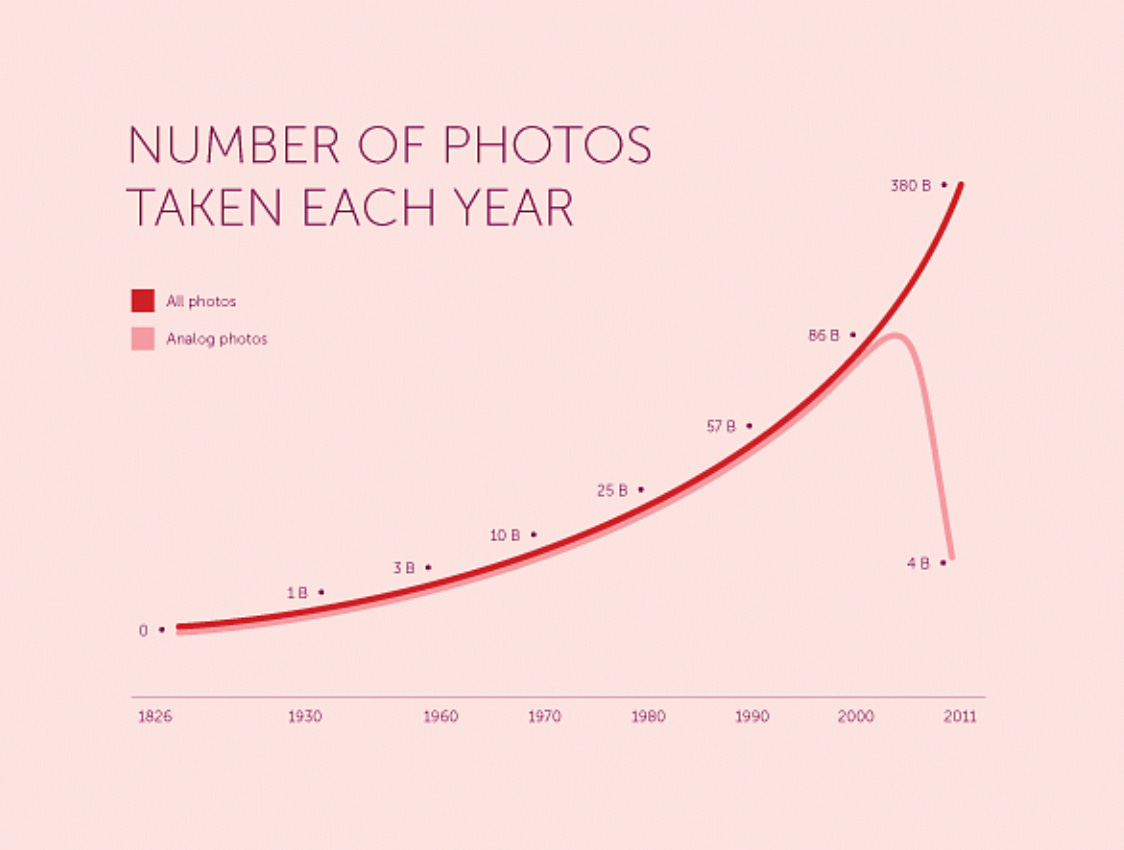

Unfortunately, this page is not very informative. I learned that 1000memories was a short-lived photo organizing and sharing website that was in operation from 2010 through 2013. It was frustrating that I couldn’t access the article with the data that everyone seemed to be relying on. Fortunately I thought to utilize the “Internet Archive” which, if you’re not familiar with it and couldn’t guess from the name, archives web pages on the internet. Using that tool, I was able to retrieve a snapshot of the web page as it appeared when published in 2011. The author of the article, one of the co-founders of the website, offered the following graph:

The dazzling pinkness of this graph initially distracted me, but with time I was able to concentrate on its content. It says that no photos were taken prior to 1826 (that seems reasonable), while 1 billion/year were taken in 1930, 2 billion/year in 1960, and so forth. You’ll notice that around the year 2000, the number of analog (i.e., film) photos dropped precipitously as digital cameras and, later, smartphones, became popular. That looks reasonable too.

Despite its apparent reasonableness, I wondered how the author produced these numbers. Acknowledging that there is a “surprising dearth of direct data,” he guesses that at most a few million photos were taken prior to the invention of Kodak’s Brownie camera in 1900 which brought photography to the masses. For the 20th century, the estimates were made using a (pink) mathematical formula:

The article posits that the number of film photos can be estimated using data on the number of Kodak employees each year and the volume of silver halide (a key ingredient of film) produced. Unfortunately, the article provides neither the employee data nor the production data, links to either data source, nor an explanation of the actual formula (or function) used to estimate photo volume from those two sets of numbers, if they ever existed. While the article was groundbreaking in its use of the color pink, it is a complete letdown for those of us looking for a reason to believe its numbers.

A brief interlude

By this point in my research, I had learned something important, however. Seemingly every article in this weird little corner of the internet provides an obligatory mention of the first photo ever taken, View from the Window at Le Gras, created by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. In the interest of conformity, I provide my reference here:

I’m sure you’ll agree that this photo would not have received many “likes” on Instagram. Apparently Nicéphore didn’t have a good internet connection and never bothered to upload it, thereby avoiding the cold reception this photo might have received today.

Back to the story…

Crushing disappointment

I don’t think I can adequately convey the disappointment I experienced as I learned that 1000memories wasn’t the kind of resource I could rely on. I needed something better for my vast readership. In a panic, I continued to ponder how I could estimate the number of film pictures taken.

At last, I came up with an idea. What if I could find data on the volume of film production during the 20th century? Maybe I could use that to estimate the number of pictures taken.

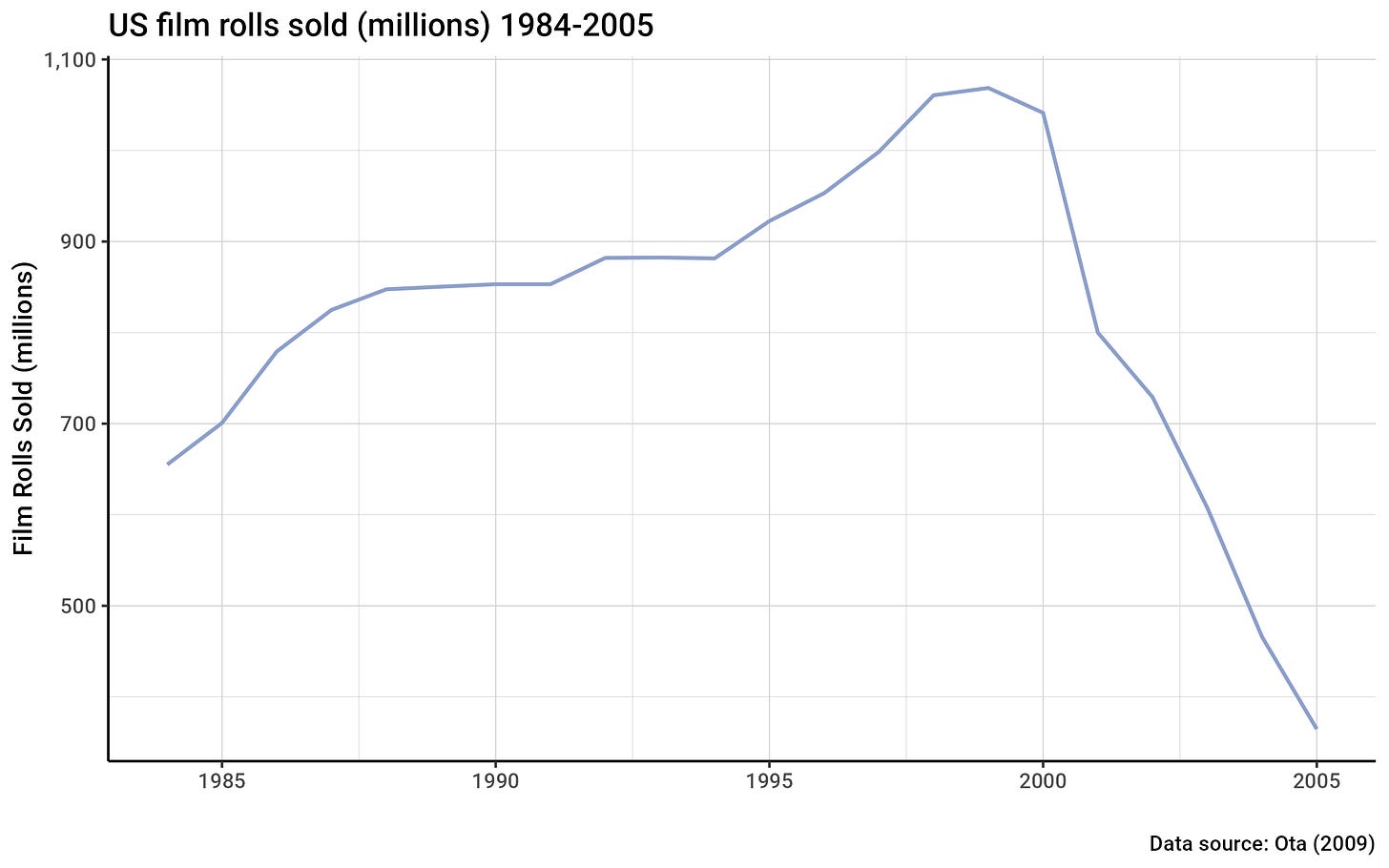

This sounds straightforward, but even after running enough searches to burn out a small bank of Google’s servers, I came up empty-handed. Until…I looked in Google Scholar for academic research on the topic. I eventually found (sort of) what I was looking for, a 2009 paper titled Estimation of the demand function in a declining industry: The case of the U.S. photographic film industry by Rui Ota of the Department of Economics at Chiba Keizai University in Japan. This paper presents a graph showing the number of rolls of film sold in the US from 1984 through 2005, with sales data gathered from a variety of sources including Mediamark Research: Sports and Recreation Report, Wolfman Report, PMA International Trend Report and PMA Photo Industry 2006. Periodicals, I admit, I rarely read.

The data in the graph were broken down by type of film (35mm, instant, one-time-use camera, etc.) with no accompanying table. I estimated total sales by year from the published figure and made my own graph of the total number of rolls produced in the US by year:

It’s easy to see from this graph how film sales increased steadily over the 80s and 90s, peaking in 1998 and 1999, and then declining precipitously as digital photography caught on. The early 2000s were not a good time to be in the film manufacturing industry.

Finding these data felt like a bit of a triumph, but it actually didn’t help me solve the problem of figuring out how many film photos were taken globally. The reason is that these data reflect only US sales. Back in the film days, just like today, photography was an international affair.

One data point I can live with

Fortunately, I found another academic paper that (partially) bailed me out. Kodak vs. Fuji: The Battle for Global Market Share (Finnerty, 2000) reproduces data presented in a Kodak annual report for 1998. At the time of the report, Kodak was nervous about the coming impact of digital photography on its vast film market, so it was looking at the potential for increased international sales. Quoting Finnerty:

Kodak believes that the future of photography, in addition to advancing technology, is in getting more people to take pictures. To that end, they state in their 1998 annual report: “What if households in developing markets shot a full roll of Kodak film each year? The gain would be immense.”

History tells us that “developing markets” (a very bad pun in this context) didn’t rescue Kodak. In the years to come, many more people would take many more photos, but almost none of them would use film to do it. Kodak declared bankruptcy 14 years later, although it remains in business today manufacturing other stuff including pharmaceuticals.

But I digress (once again). In making its point about potential international growth for film sales, Kodak estimated the total number of rolls of film sold in 1998: 2,219,300,000 rolls. Knowing the number of rolls sold still doesn’t tell us how many pictures were taken, however, because each roll of film would be used to take multiple exposures (pictures). Rolls of film at the time were typically available in two sizes: 24-exposure and 36-exposure. Ota’s paper states that 24-exposure film accounted for about 74% of sales. If 74% of rolls were 24-exposure, and the remaining 26% were 36-exposure, then the average roll would have contained 27.1 frames.

Multiplying the number of rolls sold in 1998 (2.2193 billion) by 27.1 frames, produces an estimate of 60.1 billion exposures. Of course, there would be some wastage. Not every frame would be taken and developed. But since film wasn’t cheap, I’ll assume that the rate of wastage was fairly low.

Subjects to the caveats I mention above, I estimate that that about 60.1 billion pictures globally were taken on film in 1998. You can quote me, internet.

What about all the other years of film history? I considered using Ota’s US sales data to estimate global photo volume. For example, US sales in 1984 were about 62% of the sales in 1998, so we could multiply 60.1 billion frames by 62% to estimate global pictures taken in 1984. However, this would assume that the pattern of sales over time in the US accurately reflected global sales and that the ratio of global to US sales remained constant over time. These assumptions seem a bit shaky to me. Additionally, we still wouldn’t have estimates of sales made or pictures taken in the years preceding 1984.

Given the difficulty of making an estimate of film use in any year, I’m content to have a fairly respectable estimate for even a single year: 1998. Since this year represented the peak of film usage, at least in the US, it’s potentially useful. Let’s go with it and see where it leads us.

How many photos are we taking today?

Leaving the dusty archives of history behind us with the one data point we were able to resurrect, what can we learn about today’s picture-taking volume? I spent some quality time with Google once again to compile some estimates. I learned that most of the estimates come from marketing companies that are trying to make money and are somewhat reticent about sharing their results with freeloaders like me. I found one firm that offered to sell a nine-page report titled 2021 Worldwide Image Capture Forecast: 2020 – 2025 with four tables and four figures for $1,999. I have decided to pass on this offer for now, but will revise this post accordingly if I somehow lose my mind and purchase the report.

In the meantime, I will rely on the publicly available estimates which appear to be survey-based and tend to fall in the same range. A 2022 article seems to be the best of the bunch. It presents market research estimates of the number of photos that will be taken globally:

2022 1.50 trillion

2023 1.60 trillion

2024 1.72 trillion

Let’s use the estimate for 2024 (1.72 trillion photos per year) and see where it leads us.

Let’s go to the moon

It’s kind of hard to wrap your mind around a number like 1.72 trillion. To put it in perspective, it works out to more than 50,000 photos per second. That’s a lot! And how does that compare with the number of film photos taken? Well, based on the one data point we were able to rescue from the annals of photography, we can make the following statement with reasonable confidence:

In the year 2024, every 13 days the world takes as many photos as were taken globally in 1998 at the peak of film photography.

Let’s look at it another way. Suppose we printed on photo paper every picture taken in 1998 and every picture taken in 2024. I know…it would be impossible to do this without a printer jam, and the cost of ink would be astronomical. But this is a thought experiment, so go with it.

I measured the thickness of some photo paper in my closet and I counted 86 sheets per inch. Given that, if we stacked up all the 1998 printed photos, they would make a pile 11,030 miles tall. If we laid the pile on end, it would reach almost halfway around the earth (about 44% of the way). Notably, a lot of it would get wet because it would have to go through an ocean or two.

If we stacked up our 2024 photos vertically, the pile would be about 315,657 miles tall, soaring beyond the orbit of the moon. If we stacked every day’s pictures as the year proceeds, we’d reach the moon around October 2nd.

If you stuck with me through the end of this post, you now have a few fascinating facts you can share at the next party you attend. Perhaps we should throw a nerd celebration on October 2nd and talk about it.

☕️Hello Dave, this is the first article from your Substack that I have read.

My reading experience went like this:

•Intrigue.

•Curious, but measured reading.

•Spit-take from unexpected biting laughter.

•Wipe coffee off phone to continue reading.

•Repeat.

Based on this experience, I am looking forward to listening to more of your statistical nonsense at the party on October 2nd.

Perhaps I’ll bring a camera.

"fascinating facts" may be a wee bit of an overstatement on two accounts! But, I am, in "fact" "fascinated" by the "fact" that you spent as much time as I estimate went into the detail -- and humor -- of this piece. Have you thought about exploring the number of humans (or other photo-taking species) that might impact the analysis (e.g., toddlers who get ahold of parents' cellphones and push buttons, dogs that step on the phones while licking the gravy off of the phone, etc.)?