Miss Sunshine

It's hard to imagine anyone having a worse experience on an elevator than Betty Lou Oliver. On July 28, 1945—just a week before the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima—Captain William Smith attempted to land a B-25 bomber at LaGuardia Airport in New York City. Lost in dense fog while circling the city, his plane slammed into the Empire State Building and exploded, killing all aboard the plane and 14 people inside the building, and leaving a gaping hole between the 78th and 80th floors.

Twenty-year-old Betty Lou Oliver was working as an elevator operator in the Empire State Building. Moments before the crash, the door of her elevator opened onto the 75th floor. The force of the plane's explosion blew her out of the elevator car and onto the hallway floor, leaving her seriously injured with fractures and burns. Three young women applied first aid and managed to move her onto a neighboring elevator so a second operator could take her downstairs for help. One witness reported that, "just as the elevator doors closed, he heard the elevator cables snap with a crack like a rifle shot, and the car fell toward the sub-basement"—a 1,000 foot drop.1

Firefighters cut through the sub-basement wall to reach the elevator car, "fully expecting to find the occupants dead".2 Instead, they discovered Ms. Oliver and the elevator's operator alive, though in terrible condition. Ms. Oliver eventually recovered after spending 18 weeks in the hospital and was able to walk with the aid of leg and spine braces and crutches.

During her recovery, she gained celebrity status, dubbed "Miss Sunshine" for her positive attitude. On November 27, the day of her discharge:

...she was wheeled by her smiling husband to an elevator that took them to the first floor, and from there to a waiting auto. As she entered the elevator, Mrs. Oliver laughed and said: "I suppose I should be afraid of these things, but really I'm not."3

Nine months later, on August 25, Ms. Oliver gave birth to her first child.4 She eventually had three children and seven grandchildren, passing away at the age of 74 in 1999.

Her survival after the elevator's 1,000-foot drop has been variously attributed to safety equipment that slowed the cab's descent5 or to cushioning from fallen cables and a pocket of air that developed below the floor of the cab.6

Restoring the "luster of strangeness"

Elevators today are extremely safe—arguably the safest way to transport a person from Point A to Point B—so stories like this are exceedingly rare. As a result, we rarely think about the elevator and how it has transformed our society.

While anthems have been written to jet travel, locomotives, and the lure of the open road, the poetry of vertical transportation is scant. What is there to say, besides that it goes up and down?7

Elevator historian Andreas Bernard (yes, elevator historians exist) writes in his book Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator, "The following pages will attempt to restore to the elevator, an object that has become dull and inconspicuous in the twenty-first century, the luster of strangeness." By this he means that when thinking about "an object that is so omnipresent and unspectacular today" one must:

...see objects not as they appear to the daily user, but as the inventor saw them when they first took shape. He needs the unworn eyes of contemporaries, to whom they appeared marvelous or frightening.8

Let's see if we too can restore the strangeness.

All safe, gentlemen. All safe

Since the time man has occupied more than one floor of a building, he has given consideration to some form of vertical movement.9

Thus intones the fourth edition of The Vertical Transportation Handbook, the elevator industry's bible. Various forms of powered vertical transportation have been in use since at least ancient Roman times. The Liberty Elevator Company informs us that "there were 24 elevators used in the Roman Coliseum, which were manually operated by over 200 slaves".10 This was well before the invention of elevator music, but that probably didn't matter because these elevators were used primarily to lift lions, not people.11

Beginning in the Middle Ages, winches were employed to transport materials and equipment in mines. But these machines suffered a major weakness: the hemp ropes and chains used to support payloads frequently broke. They broke so frequently that, until 1859, German mining regulations prohibited miners from riding in the freight baskets.

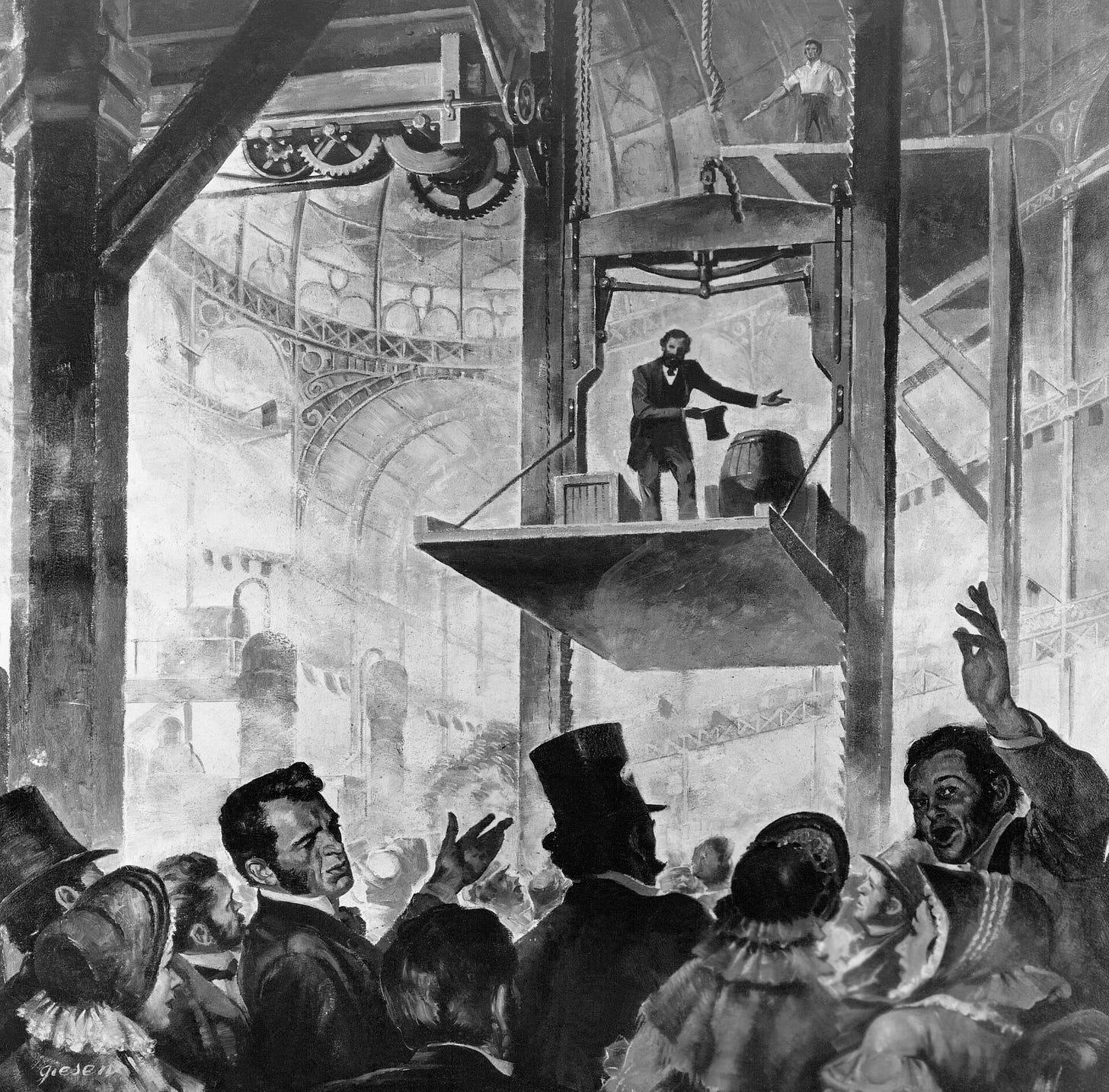

This problem needed to be solved before elevators could be safely used to transport people in buildings. The solution came from Elisha Otis, who invented the "safety elevator" and later founded the Otis Elevator Company, the world's largest manufacturer of elevators, escalators, and "travelators" (the technical term for moving walkways—feel free to use it to impress your friends). In 1854, Otis demonstrated his invention in dramatic fashion at an ongoing exhibition in New York City.

He installed a platform on guide rails on which he had himself hoisted into the air before the onlookers. When the platform had risen to its maximum height, to [the audience's] horror, he severed its suspension cable. But instead of plunging fifty feet to the ground, the elevator stopped short after only a few inches of travel. “All safe, gentlemen, all safe.”12

As one historian of the elevator put it, “Although people had been building hoists for at least two thousand years before that, their hoists had the serious fault of falling to the bottom should the lifting cable break. But Mr. Otis invented something that no one had ever seen before. He built a hoist equipped with an automatic safety device to prevent the car from falling.”13

Otis's demonstration received widespread fame, convincing the public that elevators could be safe. Or so the story goes. Bernard's book claims that the demonstration received almost no publicity at the time, let alone widespread fame. He also presents evidence that the illustration above, which today is reproduced in many articles about the history of elevators, was in fact drawn in 1978 at the behest of the Otis Elevator Company. Bernard states flatly, "Without doubt, the ex post facto valorization of this primal scene has to do first and foremost with the business interests of the world’s largest producer of elevators."14

While I take no stand on such revisionist claims, the fact remains that elevator installations became more and more widespread in the second half of the 19th century following Otis's performance. In the U.S., elevators became a standard feature in large hotels on the east coast by the 1860s, and by the 1870s, elevators were being installed in all new multistory buildings.

However, these buildings were not yet skyscrapers.

In New York around 1875, the elevator enabled an increase in building height to about eleven stories....Eleven or twelve stories, however, was their vertical limit, since for any additional stories the walls of the lower floors would have to be so massively expanded and stabilized that any gain in space and rent would be negligible....This dilemma was famously solved at the beginning of the 1880s...by the development of steel frame construction, which greatly increased the potential number of floors by transferring the load-bearing function of masonry walls to a steel skeleton.15

By the end of the 1800s, steel-framed skyscrapers of around 20 stories were being constructed, and their heights have continued to increase. Today, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai is the world's tallest building. It is more than a half mile in height, contains more than 150 floors, and is served by a bank of 46 elevators.

In the words of New Yorker writer Nick Paumgarten:

Two things make tall buildings possible: the steel frame and the safety elevator. The elevator, underrated and overlooked, is to the city what paper is to reading and gunpowder is to war. Without the elevator, there would be no verticality, no density, and, without these, none of the urban advantages of energy efficiency, economic productivity, and cultural ferment. The population of the earth would ooze out over its surface, like an oil slick, and we would spend even more time stuck in traffic or on trains, traversing a vast carapace of concrete.16

Turning buildings upside down

The introduction of elevators had an interesting side effect: they inverted the way people thought about the height of buildings.

Before elevators, buildings rarely exceeded six stories—simply because people didn’t want to climb more stairs. The lower floors were considered the most desirable and got the highest rents because less effort was required to reach your office, apartment, or room. Upper floors were not only difficult to get to, they were considered unhealthy. This belief persisted even as taller buildings were being built.

In 1901, the physician Robert Dölger explained...“why we hygienists must be opposed to large buildings.” It is on account of the upper stories, “because stale air, tainted by the breath of the residents, by odors from the kitchen or the water closet, rises from the lower stories to the upper ones and it is impossible that the air even in the corridor or the stairwell, which supplies the upper floors as well, can remain clean.”17

As building heights soared and elevators provided easy access to the upper floors, attitudes shifted. Top floors became home to luxurious penthouses and corporate offices with commanding city views, while lower floors lost their former luster. The schedule of rents and purchase prices inverted accordingly, with premiums charged to those who wished to occupy the upper floors.

As risky as bowling

None of this would have been possible without continuous improvements in elevator safety. Modern elevators have four to eight cables independently attached to the top of the car, each capable of supporting the car's entire weight on its own. Emergency braking systems back up the cable systems, preventing drops of more than a few feet. Other systems avert injury from closing doors.

How well do these systems work?

According to industry statistics published in 2020, there are about one million elevators in the U.S. with an estimated 20 billion passenger trips per year.18 Statistics on passenger deaths are seldom studied, probably because they are so few of them. The most thorough study I could find was conducted in 2013 by a construction safety organization. For the period 1992-2009, it found an average of 10 passenger deaths per year.19 This means that your chance of dying on any given trip is about 1 in 2 billion. By comparison, you are about 2,000 times more likely to be struck by lightning over a year's time than to die when you enter an elevator.

Maybe you're worried that the supporting cables will snap and you'll fall from a high floor, as in the 1945 Empire State Building incident. Unless an airplane crashes into your building, this is extremely unlikely.

Thriller movies often show an elevator plunging down a long shaft in a freefall, but that type of elevator accident hasn’t happened since 1932 when a cable-operated elevator fell down a shaft in Brazil.20

OK, so maybe you won't die in an elevator. But what are your chances of being injured? Data on elevator injuries are available from the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) which conducts an ongoing survey of emergency room admissions as part of its injury surveillance system. In 2023, emergency rooms in the U.S. treated an estimated 12,000 injuries caused by elevators and wheelchair lifts (these are lumped into a single category).21 This is roughly the same as the nation’s volume of bowling-related injuries.

As a final note, the CPSC data indicate that most of the elevator injuries are the result of trips, slips, and falls that occur while entering or exiting the elevator rather than from elevator malfunctions. Even so, if you’re amped up on risk and regularly ride an elevator to your favorite bowling alley, you might want to reconsider your lifestyle choices. Be safe, my friend — I can’t afford to lose any subscribers.

K blows top

OK, so maybe you won't get killed or injured, especially if you watch your step getting in and out of the elevator. But what about getting stuck on your elevator ride? This happens with some frequency in the movies. For example, consider the 1987 movie Dark Tower in which "an architect, a security chief, a parapsychologist and an exorcist face evil in a Barcelona skyscraper."22 I'd advise against even entering an elevator with a foursome like that aboard, but even if you did, your chance of getting stuck with them are low. According to industry estimates, only 1 in 100,000 elevator rides get stuck.

(As an aside, I considered watching Dark Tower as part of my research for this article, but was dissuaded by one viewer's review: "By the end you'll wish you had a tall building to jump off".)

So despite what you see in the movies, it's rare to get trapped in an elevator. But it does happen. In fact, on one occasion a stuck elevator almost caused World War III.

OK, that's a bit of an exaggeration, but it is an interesting story. In the Fall of 1959, the U.S. president, Dwight Eisenhower, invited the leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, to visit America in an attempt to ease tensions at the height of the Cold War.

After spending a few days in Washington, D.C., Khrushchev arrived in New York City. According to a contemporary news account:

A scramble out of a stalled elevator and a trudge upstairs from the thirtieth to the thirty-fifth floor of the Waldorf-Astoria Towers gave Premier Khrushchev a few exciting moments on his first afternoon in New York.

The elevator power failure occurred when Mr. Khrushchev was returning to his suite after the city's luncheon at the Commodore Hotel. After a wait of three or four minutes in the walnut-paneled car, the stout Communist leader climbed out of the door to the floor, about two feet above the level of the elevator, with the aid of an upholstered corner stool. Then he cheerfully led five other passengers up five flights to Suite 35-A.

"A capitalist malfunction," he quipped.23

A later account was a bit more graphic. Reportedly, Henry Cabot Lodge, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations who was also on the stuck elevator, "had to push Khrushchev’s butt to help him climb out of the elevator".24 A more worrisome account was made by Martin Riskin who was an assistant banquet manager at the Waldorf at the time. In a book he wrote about the incident he claimed:

The Russian secret service men, the Russian KGB men, were looking at us and getting very upset, and our Secret Service were getting upset....The Russians and Khrushchev probably thought it was an attempt to assassinate him.25

World War III was averted, but the threat reemerged later in Khrushchev's trip when, on his visit to California, a planned excursion to Disneyland was cancelled due to security concerns. His subsequent temper tantrum led to the following headline in the New York Daily News:

DENIED TOUR OF DISNEYLAND, K BLOWS TOP

Fortunately, his pique was assuaged by a visit to the set of the movie Can-Can where he got to observe the filming of a "rather risqué dance scene".26

But I digress...

Dispelling myths

I feel it is my duty as a humble teller of truths to dispel some widespread myths about elevators. These truths are revealed by Elevator World, "the premier publisher for the global vertical transportation industry."27

Myth #1: The door-close button closes the door

The door-close button doesn't work. Don't bother pressing it. Once elevator doors open, mandatory timing mechanisms keep them open for a fixed interval to allow passengers to safely enter and exit the car. If you press the door-close button during that interval, the doors won't close any sooner. In an emergency, firefighters can use a key to activate manual mode to override this safety mechanisms allowing the door-close button to...well...close the door on demand. But normally, the door-close button does nothing.

Now that I've learned this, it's dead to me.

Myth #2: You can exit through the safety hatch in the roof of the elevator

You've seen it in movies and TV shows. A terrorist or bank robber or spy or even a cop climbs up on the railing inside the elevator car, reaches up to the ceiling, opens the safety hatch, and climbs up into the elevator shaft where they carry out an evil plan (or, in the case of a good guy, thwart an evildoer). This is fiction. The safety hatch is always locked and can only by unlocked from outside the car to allow emergency access by rescue personnel. If any spies or bad guys are reading this, please modify your plans accordingly.

To infinity, and beyond

Maybe the half-mile ride to the top of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai isn't long enough for you. Or maybe you need to go into space to mine some asteroids or travel to the Moon or Mars. Or maybe you just love being on elevators and yearn for a weeklong ride. If so, you need to get on a space elevator—if one ever gets built.

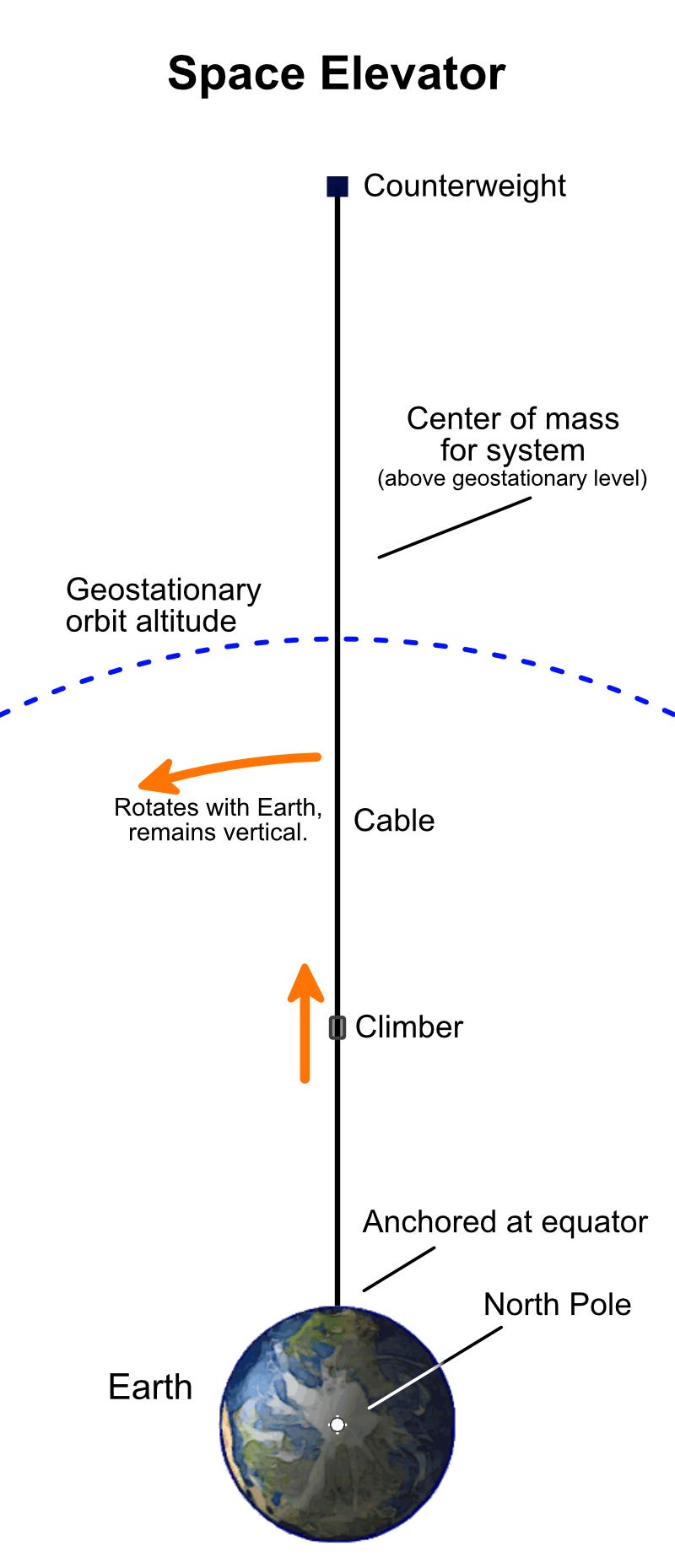

Space elevators have been a popular science fiction trope for some time and they sound like a great idea. To build one, you start with a 60,000 mile long tether. Anchor one end somewhere along the Earth's equator and extend the other end upward into space. Don't forget to attach a counterweight to the far end of the tether to keep it from falling down. The gravity that pulls on the bottom end will be counteracted by the centrifugal force caused by the Earth's rotation, keeping the tether stationary and taut.

With the tether in place, you can attach an elevator car, a "climber", to the tether at the anchor point on Earth and travel up into space. Oh, and don't forget to build a space station somewhere near the top so you can serve snacks and provide docks where space ships can load up travelers or cargo and take them to their final destination in space. Voila! You have built a space elevator!

But before you rush to your neighborhood hardware store to buy 60,000 miles of tether, you should know one thing: we don't yet have a material which can handle the forces involved. Since the tether needs to hold itself up, it must be extremely strong and extremely light, or it will tear itself apart.

While no material currently meets these requirements, possible candidates such as carbon nanotubes and single-crystal graphene are being studied in the lab.28 Large-scale production of a suitable material is the biggest obstacle to building the elevator, but there are other problems as well. These include preventing damage to the tether from space debris, dealing with large storms on Earth and magnetic storms in space, protecting people and property if the tether fails, and figuring out who's going to pay the massive bill to build and maintain the space elevator in the first place.

If these problems can be solved and space elevators ever get built, they would make today’s expensive, Earth-based rocket launches unnecessary, allowing people and materiel to be transported more safely and cheaply into space. If we installed multiple elevators around the equator, we could far surpass the tonnage that could be transported into orbit by rockets, dramatically expanding humanity's footprint in space. For this reason, NASA has been studying the idea since around 2000. In addition, the International Space Elevator Consortium, a non-profit advocacy group, is actively promoting the technology with the aim of building our first space elevator in the coming decades.

So the time may come when you can spend a glorious week riding an elevator to the stars. But if you prepare to board and discover that your fellow passengers are an architect, a security chief, a parapsychologist, and an exorcist, I'd advise turning around and waiting for the next car.

New York Times, 7/29/1945

New York Times, 7/29/1945

New York Times, 12/3/1945

New York Times, 8/26/1946

New York Times, 7/29/1945

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/04/21/up-and-then-down

Bernard, A. (2014). Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator.

Strakosch, G. R., & Caporale, R. S. (2010). The Vertical Transportation Handbook (4th Ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Bernard, A. (2014). Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator. NYU Press.

Bernard, A. (2014). Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator. NYU Press.

Bernard, A. (2014). Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator. NYU Press.

Bernard, A. (2014). Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator. NYU Press.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/04/21/up-and-then-down

Bernard, A. (2014). Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator. NYU Press.

https://nationalelevatorindustry.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NEII-Fact-Sheet-2020.pdf

https://www.cpwr.com/wp-content/uploads/elevator_escalator_BLSapproved_1.pdf

https://www.millerandhinelaw.com/blog/2024/09/elevator-accident-statistics/

New York Times, 9/17/1959

https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/otm/segments/132424-mr-khrushchev-goes-to-washington?tab=transcript

https://nypost.com/2016/10/13/that-time-the-waldorf-astoria-nearly-launched-wwiii/

https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/otm/segments/132424-mr-khrushchev-goes-to-washington?tab=transcript

https://elevatorworld.com/article/myths-and-realities-on-elevator-safety/

https://www.isec.org/faq/#HowStrong

Very interesting and actually informative article. As my Grandson and I were discussing riding our travelator (much safer than one of those elevator things) to our bowling date: perhaps the stockpile of carbon nanotubes and single-crystal graphene we've stored in Carlsbad Caverns would be useful after all! Thanks to your article we are certain the International Space Elevator Consortium (INSECT) is the perfect spot to unload this stuff.

Thanks for writing a very informative, interesting, and useful article. Now I can save time by not seeking out the "close door" button. I also appreciate your keen sense of humor. However, I am fearful that the image of K exiting the stuck elevator will haunt me each time I enter an elevator.