Changing times?

There's a cost for making our bodies conform with timekeeping standards.

In the zone

Timekeeping was a mess in the 1870s before time zones were implemented.

In American towns and cities, a central clock tower was typically maintained by a local jeweler or amateur astronomer who set the clock to noon when the sun appeared directly overhead….When it was noon in Chicago, for example, it was 12:19 in Columbus, 12:13 in Atlanta, 11:50 in St. Louis, and 11:27 in Houston.

In addition to local solar time, some towns and cities adopted “railroad time” which was defined by each railroad company. As a result “there were some 8,000 individual local time conventions being kept by towns and communities across the nation.”

A traveler from Portland, Maine, on reaching Buffalo, NY, would find four different kinds of ‘time’: The New York Central Railroad clock might indicate 12:00 (New York City time), the Lake Shore and Southern Michigan clocks in the same room 11:25 (Columbus time), the Buffalo city clocks 11:40, and his own watch 12:15 (Portland time). At Pittsburgh, Penn., there were six different time standards for the arrival and departure of trains.

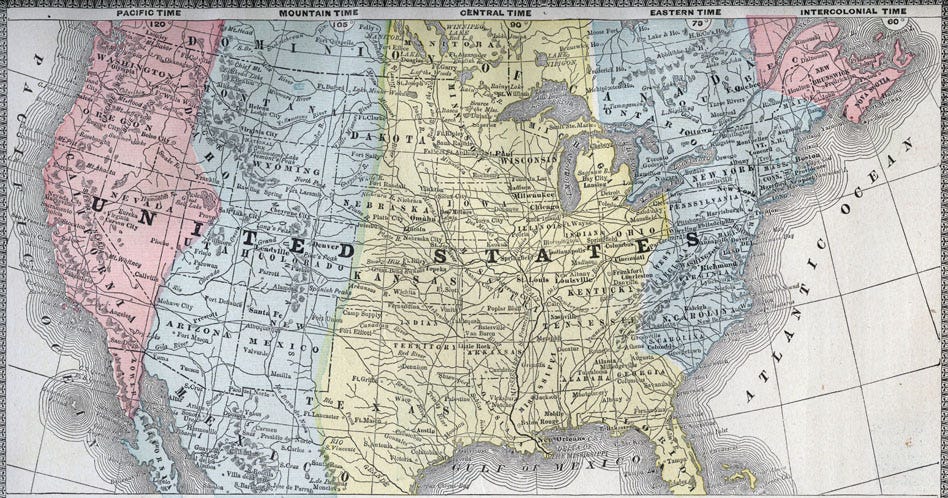

Motivated partly by railroad crashes caused by time confusion but mostly by fear that state or local governments might devise a patchwork of mandatory standards they wouldn’t like, a small group of railroad executives adopted “railroad standard time” in 1883 based on time zones that loosely resemble those we have today (note, however, the Intercolonial Zone, the pink northeastern area in the map below).

This unofficial standard was adopted within a year by about 85% of towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants, though some localities resisted until the federal government stepped in 33 years later.

Saving time

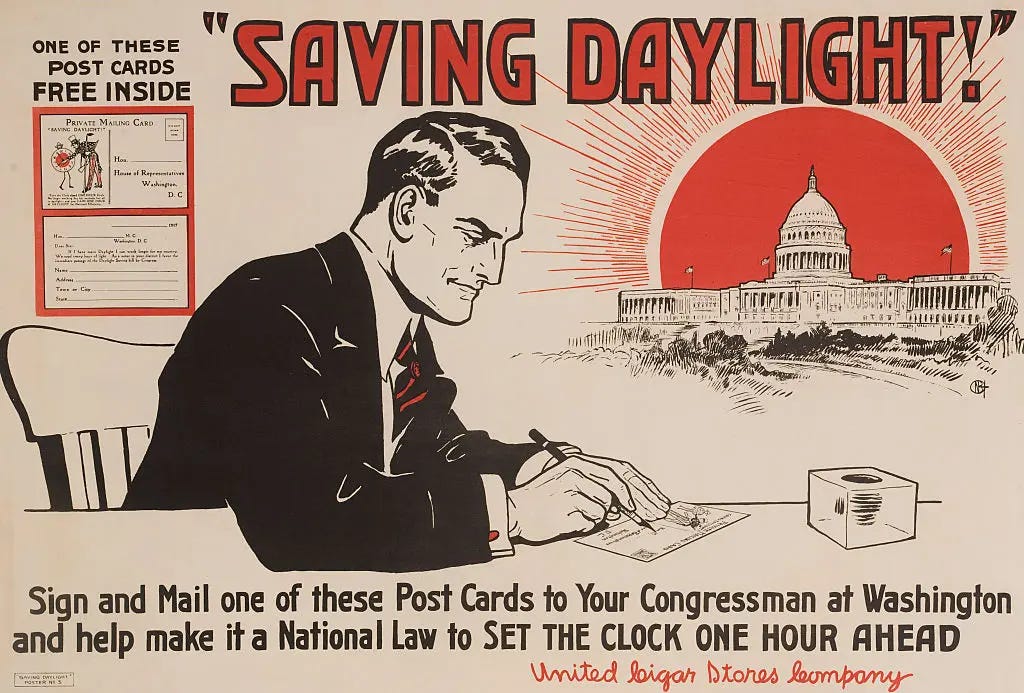

In 1918, Congress passed a law implementing our current four time zones in the continental US. The legislation also included a new invention: Daylight Saving Time (DST). Under DST, the clock is set ahead by one hour in the spring, shifting daylight one hour later with darker mornings and brighter evenings. Clocks are set back to standard time in the fall when days begin to shorten, causing lighter mornings and darker evenings. The adoption of DST in 1918 was prompted by the need to conserve fuel during World War I (it was believed that better use of the daylight hours would reduce the use of artificial light).

With the passage of the Standard Time Act in 1918, the two basic features of our current timekeeping standards were in place: time zones and DST. We’ve kept time zones in place (with some boundary changes) for the past 106 years, but we’ve had a love-hate relationship with DST. It was abolished a year after passage, in 1919, reinstated during World War II (to save fuel), abolished nationally again after the war (though some states retained it), reinstated nationally in 1966, made year-round in 1973 (again to save fuel, this time during the OPEC oil embargo), and trimmed back to a summertime policy again the following year. Additionally, several laws have been passed along the way that tinker with DST starting and ending dates. Under current law we observe DST for about eight months of the year, although two states, Arizona and Hawaii, have opted out and use year-round standard time.

Has Daylight Saving Time lost its shine?

DST isn’t popular, or at least changing our clocks twice a year is unpopular. According to an Economist/YouGov poll, 62% of Americans would like to eliminate the time changes. Among those respondents, 50% favor year-round DST, while 31% favor year-round standard time (the remainder have no preference or are unsure).

Nineteen states have passed legislation or resolutions favoring year-round DST if Congress approves it. On the federal level, Sen. Marco Rubio authored the Sunshine Protection Act in 2018 and has re-introduced it in every subsequent Congress. The act passed the Senate in 2022 but died in the House, and has stalled in the current Congress.

Most sleep experts and chronobiologists agree that the DST transition should be abolished, but oppose year-round DST. Instead, they generally favor year-round standard time. For example, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine states that “a change to permanent standard time is best aligned with human circadian biology and has the potential to produce beneficial effects for public health and safety.” Let’s see what they’re talking about.

Social jet lag

The spring DST transition disrupts by one hour the alignment between our biological clock and the clocks on our wall, watch, or phone (termed “social clocks”). Chronobiologists have named this misalignment “social jet lag”.

Each of us has a “chronotype”: “a person’s innate preference for timing of sleep and activity, as exemplified by the existence of morning and evening people (also known as larks and owls).” Chronotypes in the population are distributed on a bell-shaped curve, but regardless of your propensity, your internal clock is synchronized on a daily basis with your local solar time, primarily by sunlight but especially by morning sunlight, which triggers hormonal and other changes.

Our biological clock (i.e., our circadian rhythm) governs many of our body’s biological processes and is therefore important in maintaining our health. Social jet lag has been shown to have a variety of adverse consequences including poor sleep and impaired cognitive performance, as you might expect, but also including obesity, diabetes, impacts on cardiovascular performance, and emotional and behavioral problems. This includes an increased risk of deaths from suicide and drug overdoses.

Note that the fall transition from DST to standard time is less of a problem for your body than the spring transition. First, because the clock “falls back” an hour, you get an extra hour to sleep the night of the transition. Additionally, having returned to standard time, local solar time and our internal clocks are better aligned with our social clocks.

A surprising finding

There’s been a lot of research into the consequences of social jet lag and I only scratched the surface in my reading. But I want to tell you about two studies because their findings were so surprising.

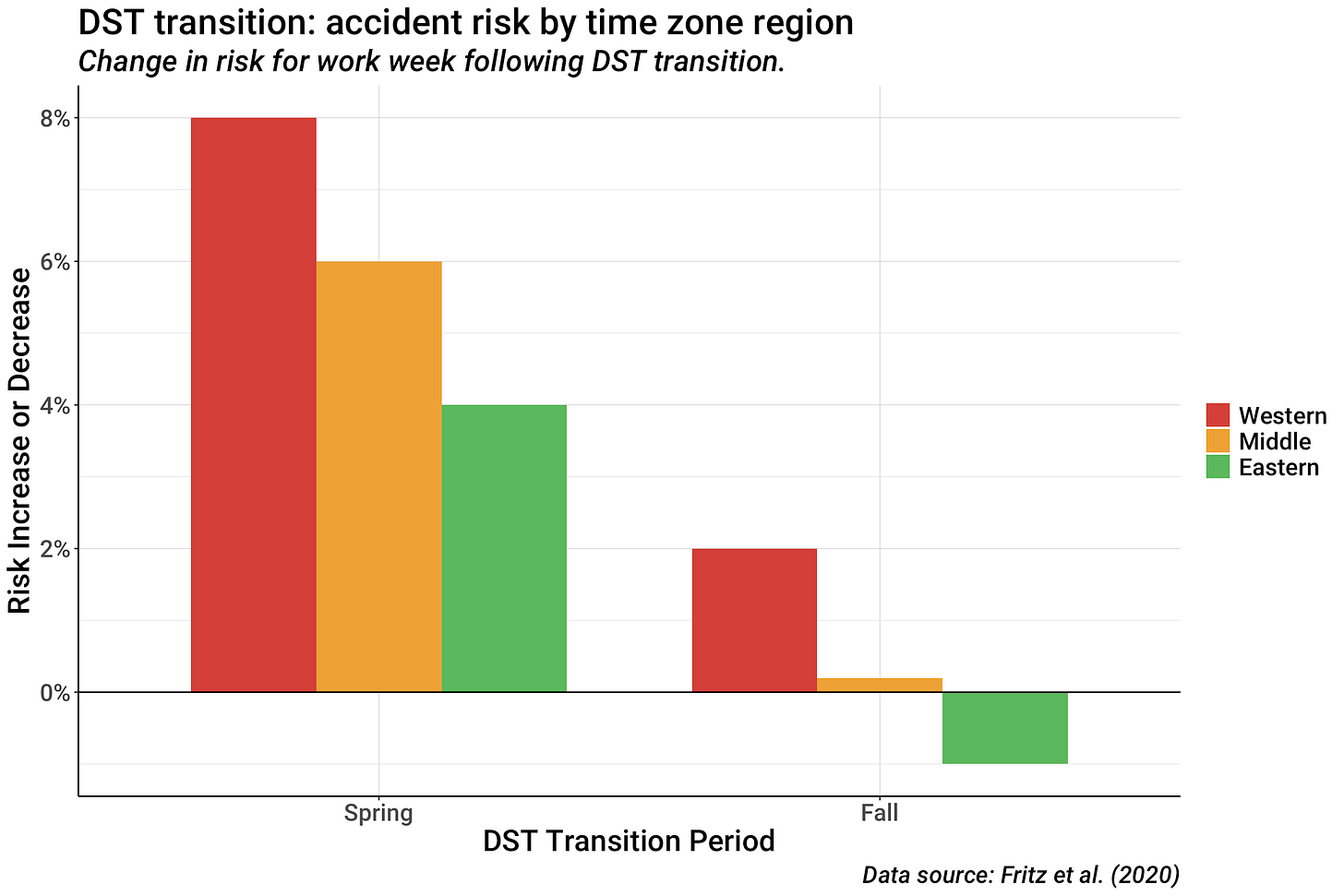

The first study had two parts. The first part used federal data on over 700,000 fatal motor vehicle accidents in the US from 1996-2017 to assess the impact of DST transitions on driving risk. The authors found a 6% increase in fatal accidents during the week following the spring DST transition. This translates into about 5.7 excess fatal accidents per day (Monday through Friday) of that week, or about 28.5 across the five days. The increased risk largely faded by the second week after the spring DST transition. In contrast, there was no change in risk following the fall DST transition.

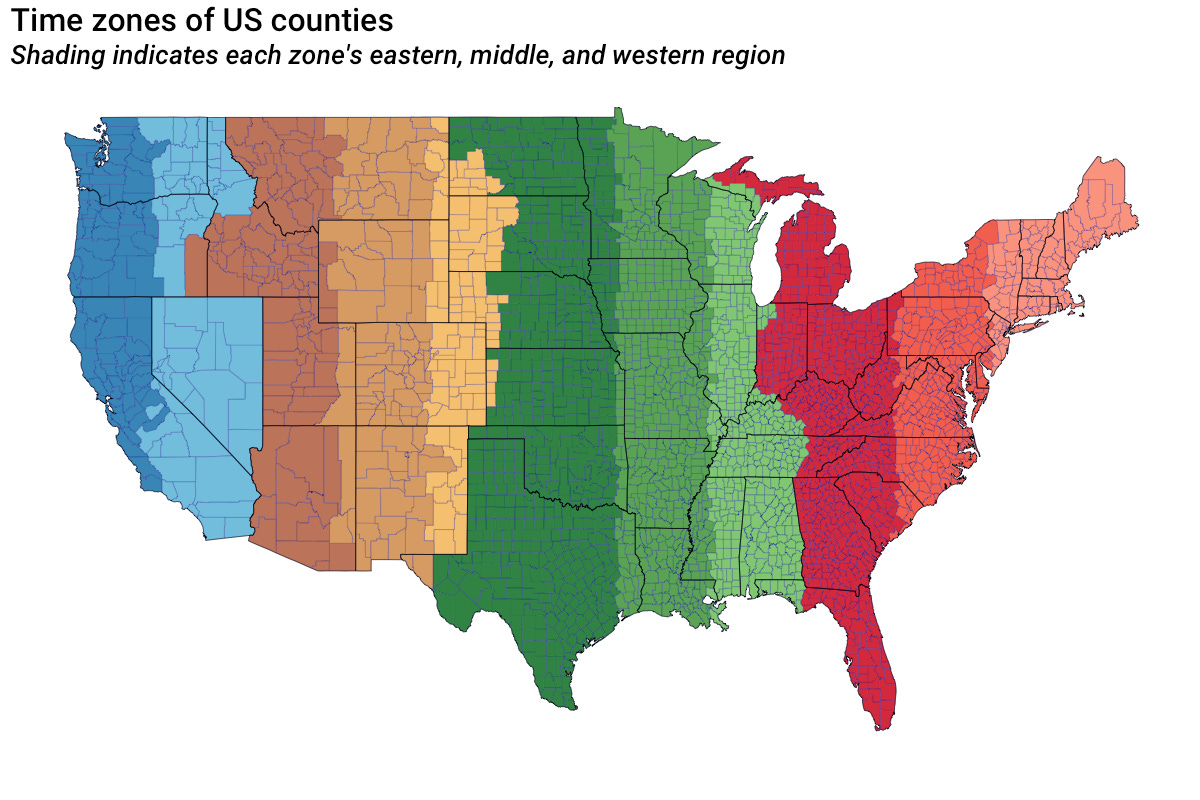

The second part of the study blew my mind. Pointing to “emerging evidence [that] suggests that circadian misalignment is more prevalent at locations further west than east within a given time zone,” the authors analyzed the accident rate by location. They divided each of the four time zones in the continental US into three regions: western, middle, and eastern, as illustrated below.

The three red regions in the eastern portion of the map comprise the Eastern time zone. The dark red section is the western region of the Eastern time zone, while the lighter shades represent the middle and eastern regions. The Central, Mountain, and Pacific time zones (the green, brown, and blue zones) are similarly divided (though the Pacific time zone has no western region).

The authors aggregated accidents occurring within the western regions, the middle regions, and the eastern regions, and then compared fatal accident rates among these three areas.

The three bars on the left-hand side of the graph show the increase in fatal accident risk within each of the three regions during the work week that followed the spring DST transition. The right-hand bars show the risk for the fall transition. The spring effects were statistically significant, but the fall effects were not.

These results suggest that the farther west you live within a time zone, the greater the risk of a fatal motor vehicle accident in the work week following the spring DST transition. Further analysis showed that a 5-degree increase in longitude moving east to west within a time zone increases risk by about 4%. The authors conclude:

These results support our hypothesis that DST-induced effects on the circadian system are more severe and harder to recover from in western than in eastern regions of a given time zone.

What?! Why would this be? Well, each of the world’s 24 time zones covers 15 degrees of longitude and by definition sunrise, noon, and sunset on the western edge of a time zone occurs almost an hour later than on the eastern edge (note that our real-world time zones don’t conform exactly to this 15-degree definition).

Since the sun’s cycle is later on the western edge, solar local time is later than on the eastern edge. According to some other studies, residents of these western regions have chronotypes that are synchronized later and are farther out of whack with clock time than residents in eastern regions, thus they should have greater social jet lag.

Chronic social jet lag

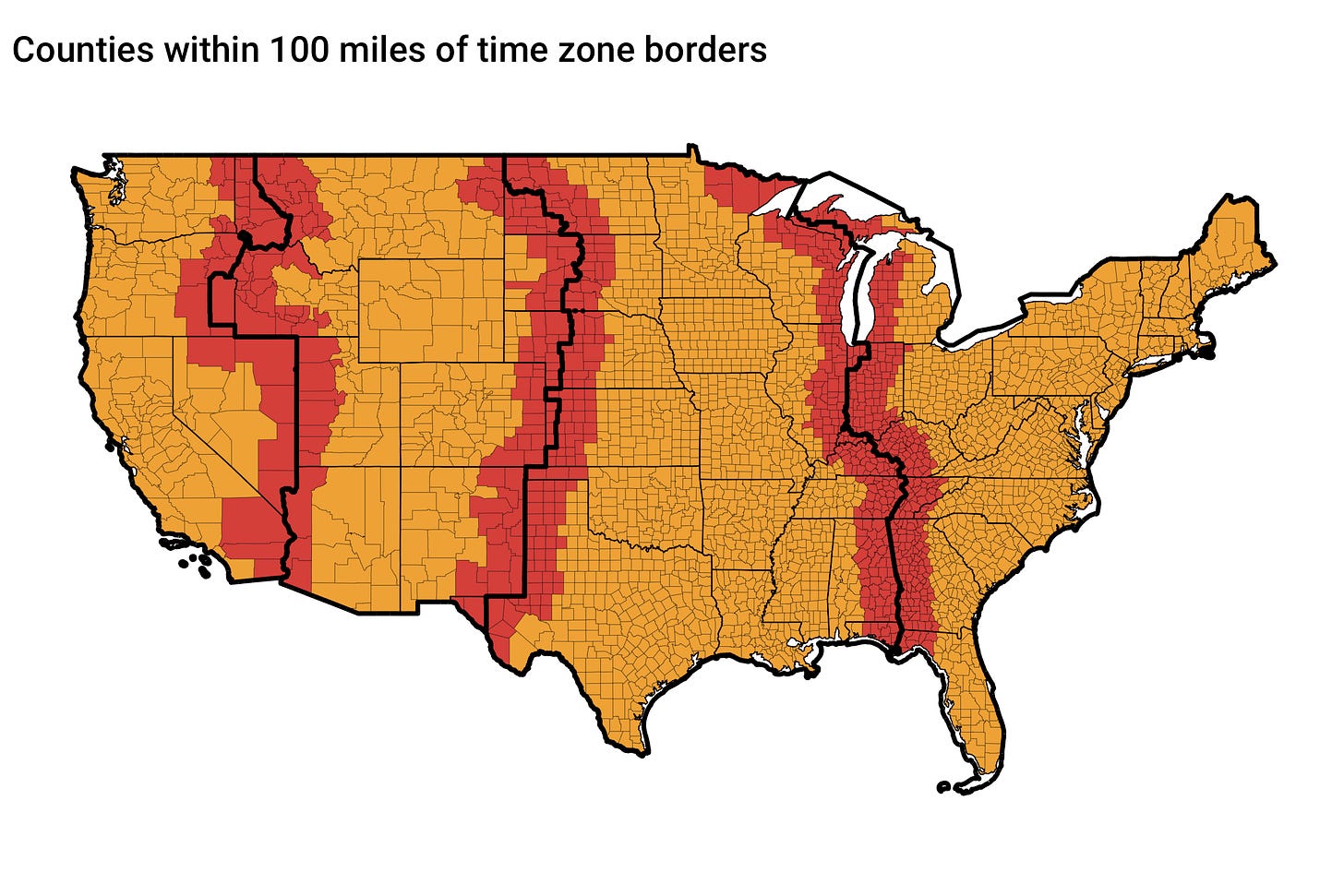

Following this line of thinking, the second study that blew my mind looked at the effect of chronic jet lag among residents in the western edge of US time zones. It focused on counties located within 100 miles east or west of a time zone border. Here’s a map of the counties they looked at.

The three black vertical lines depict time zone boundaries and the counties in red are within 100 miles of those boundaries. The counties on the right-hand side of each boundary are in the western edge of their respective time zone; the authors of the study referred to these as “late-sunset” counties. The counties on the left-hand side of the border are on the eastern edge of their time zone (“early-sunset” counties). Since residents in a late-sunset county are geographically close to their counterparts just across the border, their solar times are very similar and they should share similar chronotypes. However, their social clock times are an hour different. Moving across the border from west to east from an early-sunset county to a late-sunset county is analogous to a DST transition and the residents of the late-sunset counties should experience greater social jet lag.

The authors hypothesized that the effects of social jet lag should be greatest among individuals working in the labor force who are forced to conform with social clock time. They found that employed residents of the late-sunset counties reported 19 minutes less sleep per night than in the early-sunset counties, but there was no sleep difference for those who were not employed. They also found negative impacts on obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and certain types of cancer (breast, colorectal, and prostate): health conditions that have been linked to “circadian rhythms disruptions and sleep deprivation.”

Dicker, dümmer und grantiger

To me, these are astounding findings. Just living on the western sector of a time zone border can decrease the amount of sleep you get and increase your susceptibility to chronic health problems and life-threatening disease. Reporting on a discussion with the author of the traffic accident study, an interviewer wrote:

With all the hullabaloo over the health and safety of setting clocks forward an hour in the spring for Daylight Saving Time (DST) and back in the fall with Standard Time (ST), could where you live in a time zone actually have a more profound effect? I asked Gentry. “That’s very possible,” he said.

In light of findings such as these, we can understand why experts oppose year-round DST. Such a policy would avoid the acute impacts of time transitions, but could exacerbate the chronic impacts of social jet lag. In the words of a German chronobiologist and sleep researcher, permanent DST would make us “dicker, dümmer und grantiger” (fatter, dumber, and grumpier).

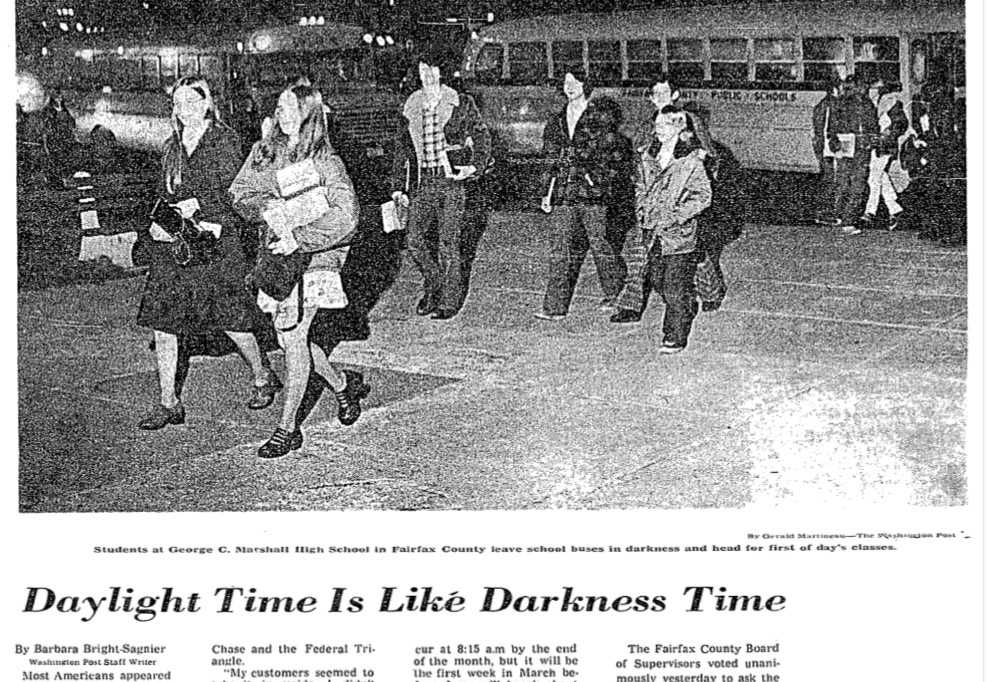

Yet this is what the Sunshine Protection Act would bring. While year-round DST will extend pleasant summer evenings, it will make winter mornings darker and more dreary. In Washington, DC in December and January, sunrise won’t come until about 8:30am under DST, and in a more northern city like Seattle it would be dark until nearly 9:00am.

If all of the evidence and the warnings from experts don’t persuade you (or Sen. Rubio), maybe this will: we already conducted a two-year experiment with year-round DST and it went so badly that it was repealed after only eight months. As I alluded to earlier in this post, a bill was passed in December, 1973 to start this experiment at the beginning of 1974 in response to the OPEC oil crisis.

Almost immediately after school began in January complaints were voiced about children having to go to school in the dark. News stories reported on children being struck by cars on the way to school, with eight school children injured in predawn accidents in Florida alone. Florida’s governor asked Congress to repeal the law and by the end of January an Iowa senator pronounced that “It’s time to recognize that we may well have made a mistake.” Public support for the experiment quickly collapsed.

A study on public acceptance of daylight saving time was conducted by the National Opinion Research Center of the University of Chicago and showed that 79 per cent of those interviewed last December favored the daylight time move. This total dropped to 42 per cent in February.

It remains to be seen whether historical and scientific arguments will be enough to forestall a move to year-round DST. If anything, we should move in the other direction and get rid of it altogether. But regardless of what may or may not happen politically, the story of how we have tried to harness time is an interesting one.

From a historical perspective, the creation of time zones is just one example of technological innovation which was intended to benefit us (by eliminating timekeeping chaos and bringing standardization) but which brought unintended adverse consequences because of biological limitations in our ability to adapt. Other examples of such technologies include the invention of processed food (which makes food more accessible but often sacrifices nutritional value) and the invention of goods and services that support a sedentary lifestyle (which contributes to obesity and chronic illnesses).

From a scientific perspective, I admire the way researchers have used powerful statistical methods to find the subtle patterns of harm we experience as the price for these and similar innovations. Unfortunately, our society’s ability to avoid such harm always seems to lag our ability to inflict it in the first place. But documenting the adverse consequences is always the first step towards improvement.

Very interesting. I had seen the studies of more auto accidents after time changes, but not the effects of being on the west side of time zones, although that does seem to make sense also. I have always been a proponent of year-round regular time (not DST), just as God intended!

You found some very convincing studies that support abolishing daylight time altogether. Take that, Sen Rubio! I wonder if anyone has studied the health effects that differing latitudes play on a person’s circadian rhythm? Differences in latitude bring hours of variation in the amount of daylight between southern and northern locations, and circadian rhythms must continually adjust particularly in the north as daylight increases or decreases by several minutes every day, year round. Maybe Sen Rubio and Congress should abolish latitudes greater than 31 degrees north (the northernmost border of the state of Florida).