Myth of infallibility?

Do polygraphs actually detect lies? A century after their invention, why are "lie detectors" still widely used despite a lack of scientific support?

Lies, damned lies, and polygraphs

How good are you at spotting a lie? Probably not very good. Experiments show that "the ability of the average person to catch a liar is typically little more than chance and rarely above 60 percent".1 Even professionals like police officers, detectives, and judges do little or no better.

Wouldn't it be great if we had Wonder Woman's Magic Lasso of Truth to compel wrongdoers to confess? Unfortunately, while humans have continually sought such a tool over the ages, we have had little success.

The colorful history of lie detection includes the use of boiling water (an honest man was thought to be able to submerge his arm in boiling water longer than a liar2); licking a hot iron (a burned tongue was a sign of lying); and swallowing a "trial slice" of bread and cheese (inability to swallow revealed deception — if true, this could make wine and cheese parties more interesting).3

Around the beginning of the 20th century in the US, the "third degree" became a popular way for US police forces to obtain confessions. (As a side note, there were two other "degrees": the first degree was interrogation at a police precinct and the second degree was more formal questioning by a detective.)

Interrogation involving the infliction of mental and physical pain to extract confessions from suspects and statements from witnesses were widespread in American law enforcement agencies across the country.…Third degree interrogation tactics...sometimes resulted in false confessions where suspects told police interrogators whatever they wanted to hear and sign statements without even reading the alleged confession written by detectives. The false confessions were often obtained after third degree tactics that included sleep deprivation and withholding food from suspects being questions for days at a time.4

The New York Times' archive between 1900 and 1920 is replete with lurid articles reporting such torture. Many of these were far from disapproving, including this example from November 16, 1919:

An "astonishing series of scientific tests"

About the time that the sheriff of Alameda County was threatening to throw uncooperative suspects out of his airplane, a new technology was being invented. William Marston, a psychologist, developed a "physiologic lie detector" that measured changes in blood pressure indicative of lying. Blood pressure is one of the four major components bundled together in the modern polygraph, which also measures heart rate, respiration rate, and galvanic skin response (that is influenced by sweating). By 1939, portable devices were available that recorded all four measurements and that were functionally the same as today's polygraphs.

The period in which the polygraph was developed coincided with a national movement to rein in use of the third degree and replace such brutality with scientific methods.

The public was no longer willing to tolerate third degree interrogation tactics of the police. Law enforcement leaders including August Vollmer [chief of the Oakland police department] and J. Edgar Hoover [head of the FBI] advocated for the use of scientific and psychological methods in police interrogations that would render the third degree unnecessary. Polygraph machines, commonly referred to as lie detectors, were developed in the 1930s and 1940s to provide more effective methods of interrogation.5

Although Marston was only one of the people responsible for the invention, he deemed himself the "father of the polygraph" and was heavily involved in promoting the machine.

Marston's first opportunity to promote his early version of the polygraph came in 1922 with the trial of James A. Frye who was accused of murdering a doctor in Washington, DC. Frye had confessed to the murder, but later recanted and claimed he was innocent. His lawyers, desperate to help their client, approached Marston after hearing about his invention.

According to Marston, Mr. Frye’s lawyers came to him and he agreed to test the defendant gratis. Marston recalled: “I gave him a deception test in the District jail. No one could have been more surprised than myself to find that Frye’s final story of innocence was entirely truthful! His confession to the Brown murder was a lie from start to finish”.6

Frye's lawyers asked the judge to allow Marston to testify as an expert witness, but the judge refused because "lie detection was not yet 'a matter of common knowledge’”.7 Frye was found guilty and his case ultimately reached the Supreme Court which ruled against admission of polygraph results in criminal cases:

We think the systolic blood pressure deception test has not yet gained such standing and scientific recognition among physiological and psychological authorities as would justify the courts in admitting expert testimony deduced from the discovery, development, and experiments thus far made.8

The court's "Frye standard" has largely held for over 100 years. Currently, 29 states exclude polygraph results as evidence under any circumstance; 15 admit the evidence if both parties stipulate to it before testing; and New Mexico permits the routine admission of polygraphs in the courtroom.9 Polygraphs are still allowed to be used for criminal investigations, however.

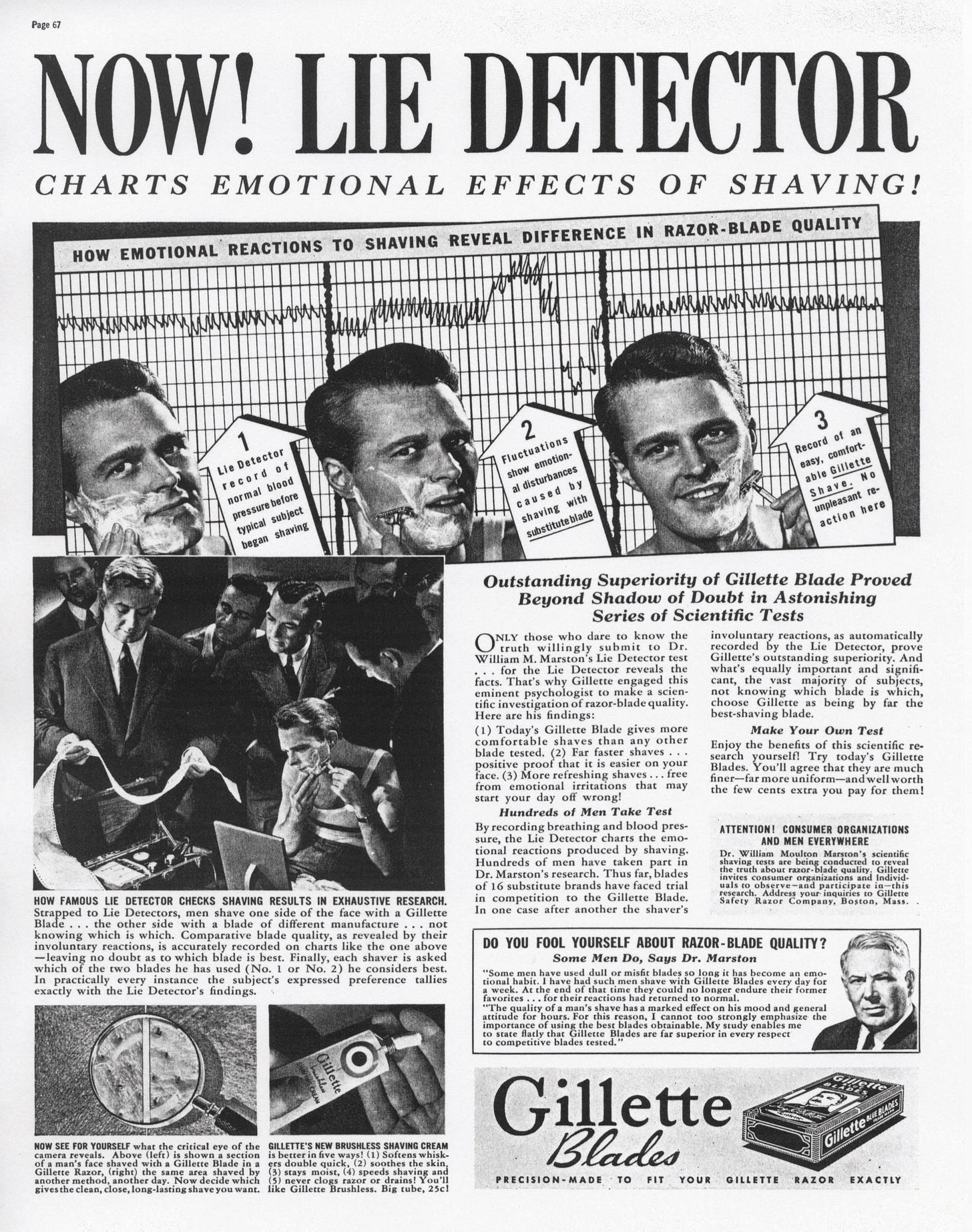

Despite this setback, Marston and others continued to promote the use of polygraphs, appearing, for example, in a series of 1938 advertisements for Gillette. These ads claimed that polygraph results proved "beyond a shadow of a doubt in [an] astonishing series of scientific tests" that Gillette razor blades are superior to the competition. Note Marston’s attestation in the lower right-hand corner of the ad below.

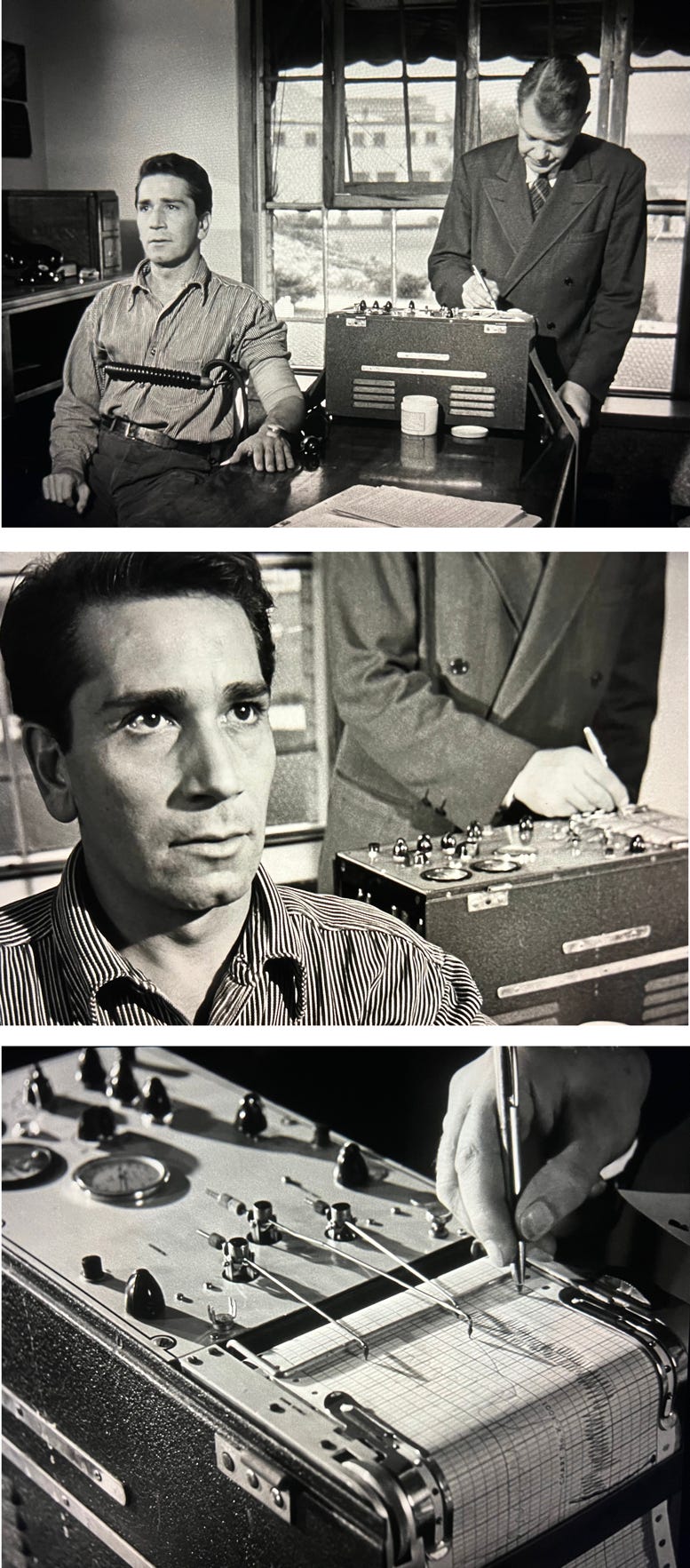

The 1948 movie Call Northside 777, starring James Stewart, showcased another use of polygraphs in a story based on actual events. Stewart plays the part of a Chicago newspaperman who helps exonerate a man falsely imprisoned for 11 years for murder. The man, Joseph Majczek (called Frank Wiecek in the movie), submitted to a polygraph to prove his innocence. The polygrapher was played by Leonarde Keeler who was one of the inventors of the modern version of the polygraph (shown below).

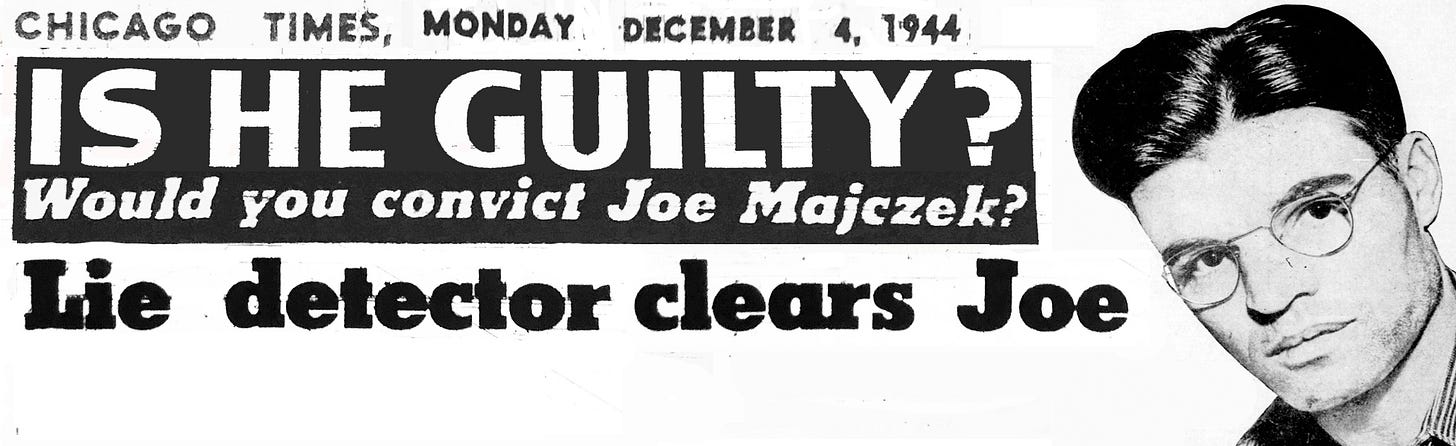

The following headline appeared in the Chicago Times newspaper when the real-life prisoner, Joseph Majczek, passed his polygraph test.

Media exposure such as this promoted the idea that the polygraph was a "lie detector" which was highly accurate. As we'll see, this myth of accuracy — even infallibility — continues today and is exploited by polygraph examiners to elicit confessions.

In a weird historical twist, William Marston was not only “the father of the polygraph”, he also worked with DC Comics in the 1940s to invent the Wonder Woman character and her Lasso of Truth.

Up to my keister!

Polygraphs gained in popularity over the decades following their introduction.

Starting in the 1930s, private businesses began to use polygraphy to monitor the honesty of their employees; in the 1960s, pre-employment screening of job applicants was introduced. Questions were asked about theft from previous employers, drug use, and the like, but then increasingly inquiries were also made about lifestyle factors such as sexual orientation and marital fidelity. Employment screening became a multimillion dollar industry, but its unregulated nature led to serious abuse and left a bad taste about polygraphy in the mouths of many.

Matters came to a head in the 1980s when President Ronald Reagan, having famously complained about being “up to my keister in leaks,” sought to introduce random testing of all federal employees and subcontractors who had access to classified information, including members of his cabinet.10

Reagan's move to subject so many people to polygraph examination provoked huge pushback, even from his own Secretary of State, George Shultz, who threatened to resign rather than be polygraphed, arguing that "management through fear and intimidation is not the way to promote honesty and protect security."11 The resulting furor led to the enactment of the Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988.

This act prohibits employers from requiring polygraph examinations for its employees or job applicants, putting a halt on the approximately one million polygraph examinations that were occurring in the US annually for employment purposes between 1981 and 1988. Notably, this act exempts local, state, and federal governments, as well as businesses that provide security services and manage controlled substances.12

Polygraphs are widely used today for a variety of purposes. According to an estimate in 2018, about 2.5 million polygraphs are administered each year.13 Though rarely allowed in court, they are used by law enforcement to assess the veracity of suspects and witnesses and to monitor criminal offenders on probation.

So-called “friendly” exams are still sometimes used in an attempt to prove innocence or bolster credibility. For example, in 2018 Christine Blasey Ford submitted polygraph results to support her claims of sexual assault during Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing.

Maybe you are planning to run a competitive sport fishing tournament sometime soon. If so, you might wish to “determine whether the winning anglers have followed the tournament rules, caught the winning fish personally, during tournament hours and within tournament boundaries, used unapproved lures, or weighted or altered the fish”. Don’t worry! For about $600 you can hire a polygraph examiner to make sure the winners don’t do anything fishy.14

The most widespread use of polygraphs today appears to be for hiring and screening employees in local and state law enforcement and in federal agencies. This includes national security screening and investigations by agencies such as the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Energy, the Department of Justice, the CIA, the FBI, the National Security Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the Drug Enforcement Agency.15

She almost "jumped out of the chair"

What's it like to be subjected to a polygraph exam? Here's an account of a “friendly” exam:

As a criminal defense attorney, I found the polygraph test useful, and I submitted my clients to testing on several occasions. There's little evidence that the polygraph is accurate, and most courts won't admit test results as evidence. But many people in law enforcement, including the FBI, believe in lie detectors, so strapping a defendant to a polygraph can be a useful tool in convincing prosecutors to drop borderline charges.

One time, I got to sit in the room as the examiner, paid by our firm, strapped and clipped the sensors to our high-strung, jittery female client....In a protocol called the "control-question test," the polygraph operator asks irrelevant questions to obtain a base-line reaction, and asks "probable-lie" questions to get a sample of a deceptive reading. My client was anxious during all of these, whether the harmless, "Are you sitting down?" or the loaded, "Have you ever stolen anything?" that is designed to embarrass the subject into lying.

When my client almost jumped out of the chair when asked if she'd stolen the particular watch in question, the examiner declared that she passed with flying colors.

That was a good result for her, but an example of how far from hard science the polygraph falls.16

The "control-question test" (CQT) described above is the most commonly used questioning technique. The examiner asks a series of yes/no questions and notes the examinee's physiological responses as they are answered. Three types of questions to asked:

Control questions invite all examinees to lie (sometimes they are explicitly directed to lie to these questions). Examples include: "Have you ever hurt someone to get revenge?', or "Have you ever lied to a person in a position of authority?" Control questions are expected to produce elevated physiological responses in all examinees.

Relevant questions ask about the offense or incident of interest. For example, a criminal suspect might be asked, "Did you steal the money?"; a potential employee might be asked "Did you ever steal from your employer?"; or a suspected spy might be asked "Did you leak that document?". In contrast to control questions, relevant questions are expected to produce strong physiological responses only in examinees who are lying or guilty.

Irrelevant questions (such as "Is today Tuesday?") are mixed in as filler and are not scored by the examiner.

[F]or the CQT to be valid, two assumptions must hold. The first requires innocent individuals to be more responsive to control than relevant questions. The second requires guilty persons to respond more intensely to relevant than control questions.17

Following this logic, the exam is scored by comparing responses on the two sets of questions. If responses are greater on the relevant questions than the control questions, the examinee is deemed guilty. Conversely, if the reactions to control questions are greater than on relevant questions, the examinee is judged innocent.

In an effort to enhance responses to the exam, examiners attempt to impress examinees before questioning begins with the power of the "lie detector".

This process often involves a demonstration in which the examinee is asked to lie about an unimportant matter, and the examiner shows the instrument’s ability to detect the lie; these demonstrations sometimes involve deceiving the examinee.18

The polygraph is not a "lie detector" at all. It records physiological responses which are sometimes associated with lying. On some occasions, those physiological responses (like increased heart rate or sweating) do coincide with lying, but they can sometimes be exhibited in the absence of lying or be absent when a lie is told.

With a few moments' reflection, you can probably come up with reasons why the underlying assumptions may not be valid. For example, if you have been wrongly accused of stealing money, you may react very strongly to the question "Did you steal the money" because you are well aware that a lot is at stake in how you answer. Conversely, if you are a hardened criminal and have been accused of such crimes repeatedly in your career, being asked whether you stole the money might not faze you at all. Worse yet, if you are a spy, you may have been trained in countermeasures that enable you to defeat the test.

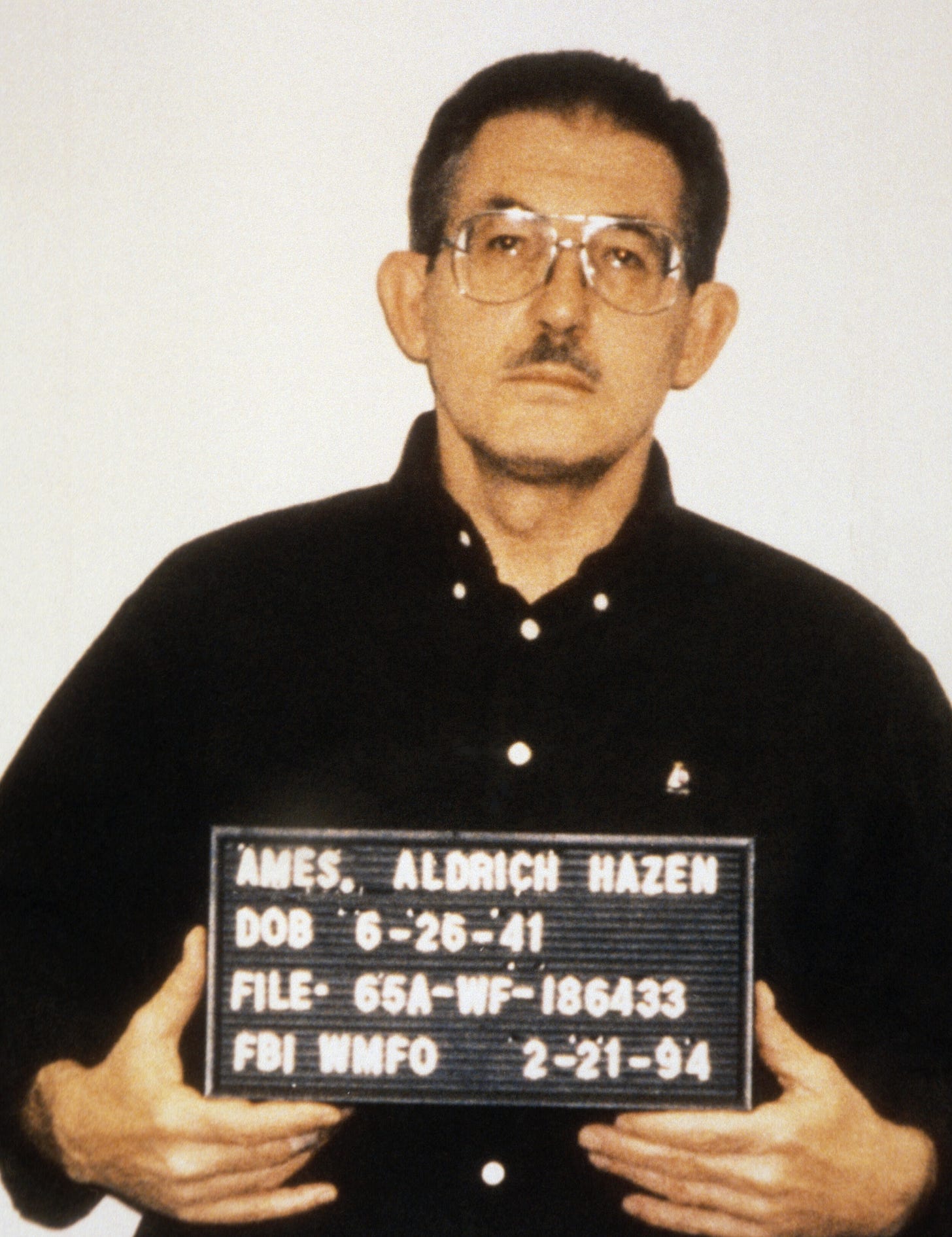

On Monday, 21 February 1994, ... the FBI arrested counterintelligence officer Aldrich Hazen Ames and charged him with spying for the former Soviet Union and later, Russia. Since beginning his betrayal in 1985, Ames had passed two CIA polygraph “tests” during which he falsely denied having committed espionage, first on 2 May 1986 and again on 12 and 16 April 1991.19

How would Ames advise others who wish to beat the “lie detector”? "Get a good night's sleep and be nice to the polygraph examiner."20

A bogus pipeline

Do we have any data that might give us a better idea of how accurate polygraphs really are in "detecting" lies? I'm glad you asked!

In 2003, the Department of Energy asked the National Research Council (NRC) — an arm of the National Academy of Sciences — to conduct a comprehensive review of research into the accuracy of polygraphs and the appropriateness of using them for employee screening (the quotes that follow are from the NRC’s report21).

The NRC assembled a team of experts who reviewed 57 studies of polygraph validity. Most of these were laboratory studies in which participants engaged in mock crimes and were tested by polygraph. They also included seven field studies evaluating lie detector use in actual criminal investigations. Almost all of the reviewed studies involved specific-incident tests in which the polygraph was used to determine whether the examinee committed a particular offense; almost none of the studies involved employee screening.

The NRC concluded that "specific-incident polygraph tests can discriminate lying from truth telling at rates well above chance, though well below perfection." The studies they reviewed placed the average accuracy at between 81% and 91%, with a midrange estimate of 86%. The accuracy measure they used indicates that if a polygraph test is administered to two people, one guilty and the other innocent, it has about an 86% chance of correctly identifying the guilty person.

However, the reviewers concluded that these indices are an "overestimate of likely accuracy in field application" due to limitations and flaws in the research. They also concluded that "[a]lmost a century of research in scientific psychology and physiology provides little basis for the expectation that a polygraph test could have extremely high accuracy."

The panel noted that the polygraph exam actually consists of two components: the interrogation by the examiner and the recording and interpretation of physiological responses.

There is essentially no evidence on the incremental validity of polygraph testing, that is, its ability to add predictive value to that which can be achieved by other methods.... For example, there is no evidence to suggest that admissions and confessions occur more readily with the polygraph than with a bogus pipeline—an interrogation accompanying the use of an inert machine that the examinee believes to be a polygraph.

With regard to the use of the polygraph in employee screening, the report concludes the following:

Polygraph testing yields an unacceptable choice...between too many loyal employees falsely judged deceptive and too many major security threats left undetected. Its accuracy in distinguishing actual or potential security violators from innocent test takers is insufficient to justify reliance on its use in employee security screening in federal agencies.

Because espionage among security personnel is rare and because the polygraph is imperfect, a high number of false positives will occur during employee screening, which means that polygraph testing will unnecessarily place many innocent employees under suspicion. The NRC ran various simulations of polygraph use under some reasonable assumptions and showed that about 200 innocent employees would fail the exam for every spy correctly identified.

Incorrectly identifying an employee as a security risk can result in enormous stress and leave a taint on their career even if they are subsequently cleared. Even for those who pass the exam, the screening process can result in self incrimination and embarrassment for behaviors which are unrelated to their job (such as marital infidelity or, in the past, for homosexuality). There is also evidence that racial minorities fail screening exams at a higher rate than White examinees.22

When polygraphs are used by law enforcement to vet criminal suspects or witnesses, false positives will be less common because the prevalence of guilt in that population is higher than among national security employees. However, false positives are of great concern in criminal investigations because civil liberties are at stake. Even though the polygraph results can't be introduced at trial, an innocent suspect who fails a polygraph exam may be charged with a crime, forced to undergo the stress and expense of a trial, risk false imprisonment, and experience vilification even if not convicted. Moreover, the police may prematurely end their investigation and fail to identify the actual perpetrator.

They scare the hell out of people

The NRC’s 417 page report is comprehensive, exhaustive, fair….and devastating. It concluded that polygraphs are too inaccurate to be used for employee hiring or screening and are of unproven benefit for police work. Given these conclusions, one might wonder why polygraphs are still so widely used.

There is a mystique surrounding the polygraph that may account for much of its usefulness: that is, a culturally shared belief that the polygraph device is nearly infallible. Practitioners believe that criminals sometimes prefer to admit their crimes and that potential spies sometimes avoid certain job positions rather than face a polygraph examination, which they expect will reveal the truth about them. The mystique shows in other ways, too. People accused of crimes voluntarily submit to polygraph tests and publicize “passing” results because they believe a polygraph test can confer credibility that they cannot get otherwise. In popular culture and media, the polygraph device is often represented as a magic mind-reading machine. These facts reflect the widespread mystique or belief that the polygraph test is a highly valid technique for detecting deception—despite the continuing lack of consensus in the scientific community about the validity of polygraph testing.

As noted above, polygraph examiners exploit this mystique. In the words of a website that advises those who must undergo polygraph examinations:

Your polygraph “test” is actually an interrogation. Even if you have not been accused of anything specific but instead face polygraph screening, you must never forget that your polygraph “test” is actually an interrogation.23

Perhaps we should listen to an authority on lying to better understand how polygraphs work:

The 1971 Oval Office tapes captured President Richard M. Nixon explaining why he had ordered polygraph screening for the White House staff: “Listen, I don’t know anything about polygraphs and I don’t know how accurate they are, but I know they’ll scare the hell out of people.”24

The polygraph is a nearly century-old technology, essentially unchanged since its debut. Over the decades, the polygraph has failed to gain acceptance among scientists or the courts. Its fundamental problem has never been solved: sweaty palms and variations in breathing, blood pressure, and heart rate are imperfect correlates of lying. People sometimes exhibit these symptoms when they are being truthful, while others fail to exhibit them when they are lying through their teeth.

When introduced, polygraphs promised a triumph of science over the third-degree's brutality. But it never had a firm basis in science. It is perhaps best understood as an interrogation dressed up with pseudoscientific theater.

The myth of the polygraph's infallibility was marketed and sold to the public and ironically has probably contributed to whatever success it has as an interrogation technique, scaring some people into confessing even before the machine is turned on. Given its shaky scientific foundation and lack of accuracy, it is hard to believe that the polygraph would be widely accepted if it were introduced today as a new invention. Perhaps the time has come to lay the myth to rest and pull the plug on the polygraph.25

https://jaapl.org/content/38/4/446.long

https://theconversation.com/is-a-polygraph-a-reliable-lie-detector-104043

https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1613&context=lawfaculty

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1086&context=crim_just_pub

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/crim_just_pub/87

https://jaapl.org/content/42/2/226

https://jaapl.org/content/42/2/226

https://casetext.com/case/frye-v-united-states-7

https://jaapl.org/content/42/2/226

https://jaapl.org/content/38/4/446.long

https://fas.org/publication/polygraphs_nsdd84/

https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/11/to-tell-the-truth-a-short-history-of-the-polygraph/

https://www.wired.com/story/inside-polygraph-job-screening-black-mirror/

https://www.polytest.org/lie-detector-polygraph-services/fishing-sporting-polygraph/

https://www.nationalsecuritylawfirm.com/polygraph-examinations-faqs/

https://www.wired.com/2006/03/the-lie-behind-lie-detectors/

http://nap.nationalacademies.org/10420

http://nap.nationalacademies.org/10420

https://antipolygraph.org/

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2016/09/20/inconclusive-lie-detector-tests

http://nap.nationalacademies.org/10420

https://www.wired.com/story/inside-polygraph-job-screening-black-mirror/

https://antipolygraph.org/

https://antipolygraph.org/

Hat tip to my friend, Jon K, who suggested I write about polygraphs. Thanks, Jon!