Where did all the Martians go?

How an astronomer used shaky data to convince other scientists and the public that a super-intelligent civilization inhabits Mars.

The Quiz

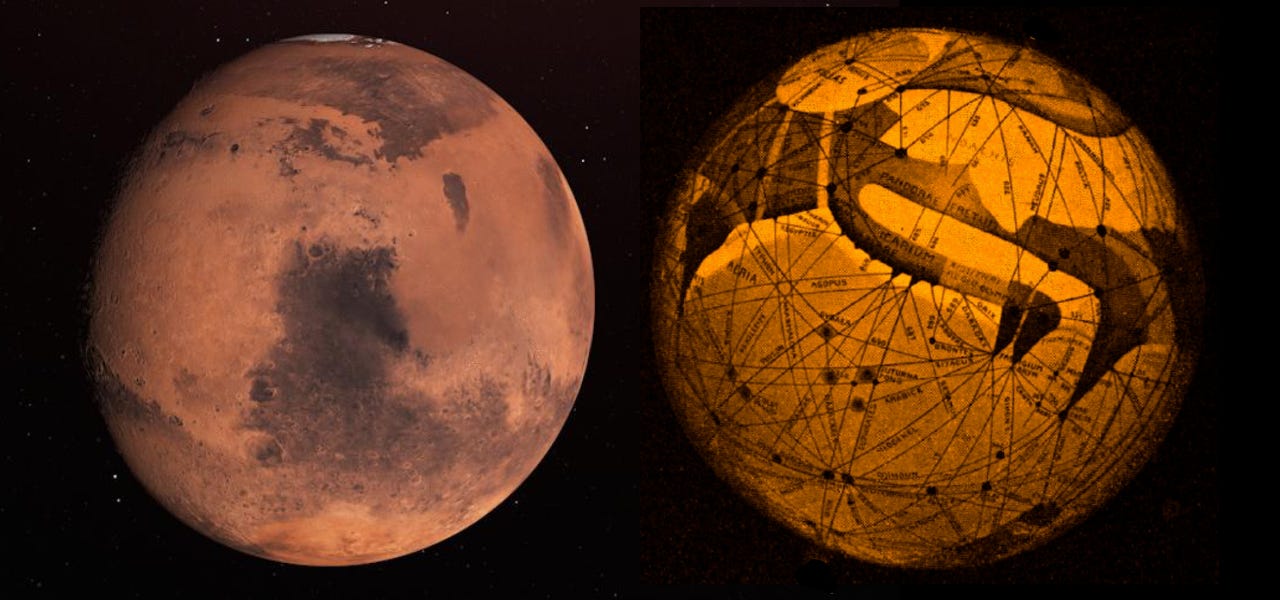

Let’s begin with a quiz: which of the following images accurately portrays conditions on Mars?

If you picked the image on the left (a photo taken by NASA’s Perseverance Rover on June 15, 2023) you are correct!

If you picked the image on the right1, you would probably have been in good company…if you had lived around 125 years ago. At that time, widely publicized research by astronomer Percival Lowell showed that Mars was covered by a massive, planet-wide system of artificial canals. These canals were built by an advanced civilization which designed them to divert meltwater from polar icecaps to irrigate the arid Martian surface and grow vast areas of vegetation. Not only that, but Lowell claimed that newly built canals appeared over successive telescopic observations, proving that Martian civilization still existed.

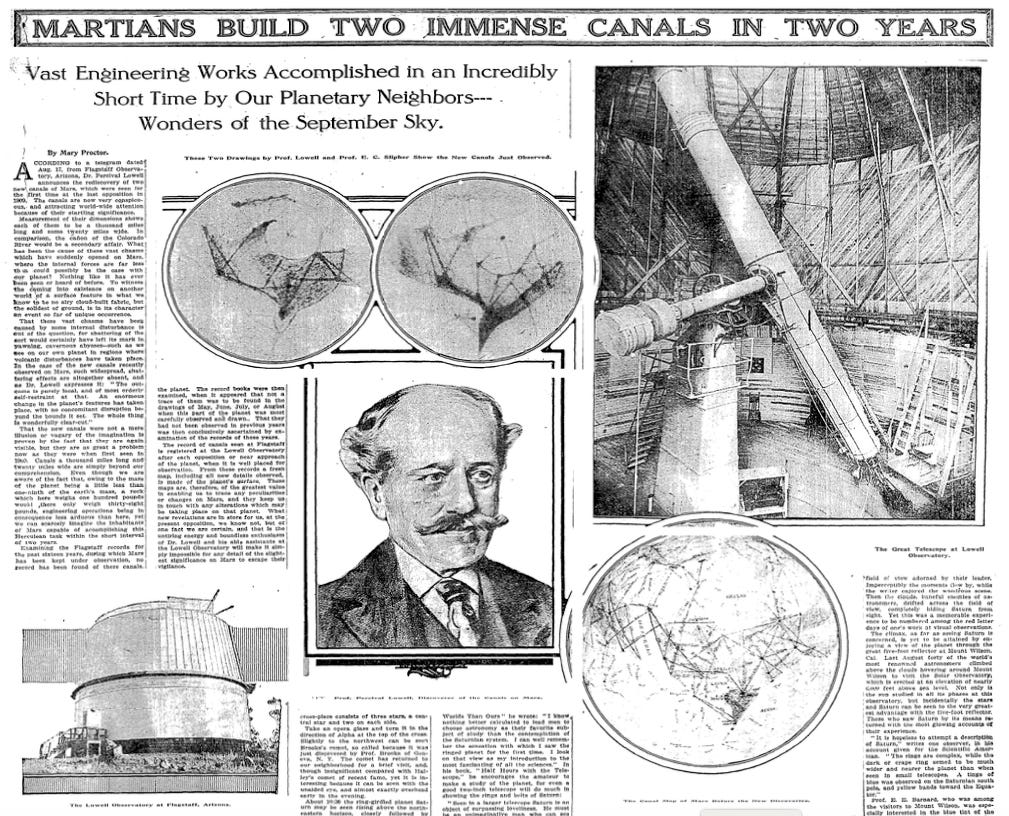

Lowell’s findings were featured in this New York Times breaking-news headline from 1907:

Lowell’s finding garnered broad coverage in the news media. This is a full-page spread from the Times in 1911 reporting on his discovery of newly-built canals:

Lowell aggressively publicized his discoveries. He detailed his evidence and theories in three popular books: Mars (1895), Mars and its Canals (1906), and Mars as an Abode of Life (1908). His “writing for popular magazines like The Atlantic Monthly, Scientific American and Century Magazine captured public attention with his arguments that the Martian canals meant there had to be intelligent life on planet.”2 “Lowell’s brilliant public lectures, his magazine articles, his tireless efforts at popularization that culminated in several books…made him and his Mars famous.”3

Alexander Graham Bell wrote of Lowell’s arguments, "[T]here is no escape from the conviction that Mars is inhabited by a highly civilized and intelligent race of beings carrying on a process of agriculture, and wringing subsistence."4

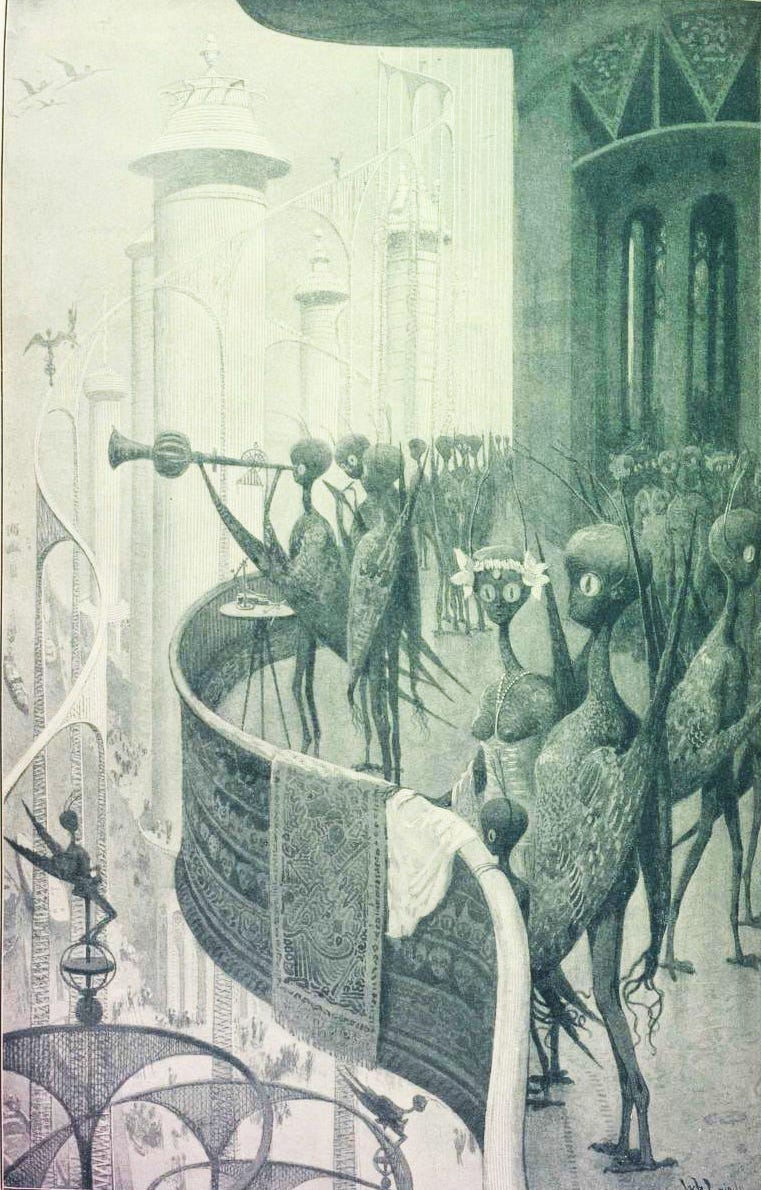

H. G. Wells’s famous 1898 novel, War of the Worlds, was partially inspired by Lowell’s discoveries. In 1908 Wells published an essay in Cosmopolitan Magazine, again inspired by Lowell, titled The Things that Live on Mars5 offering “a description based upon scientific reasoning of the flora and fauna of our neighboring planet in conformity with the very latest astronomical revelations.” This article featured an artist’s conception of Martian civilization:

“Hurry!”

Clearly, Percival Lowell was quite influential. Who was he and how did he come to “discover” life on Mars? Lowell was born into a wealthy and prominent Boston family in 1855, and attended Harvard where he showed an interest in math and astronomy. Upon graduation in 1876 he entered the family’s cotton business, spent time traveling, and published several books about Asia.

Beginning in 1877, several reputable astronomers reported seeing channels or canals on Mars. In 1893 Lowell was given a book by Camille Flammarion, a French astronomer and prolific author, which compiled nearly every known map of the canals of Mars.

He read Flammarion’s book “with lightning speed” and scrawled upon it the imperative “Hurry!” He would need his own observatory, under clear, clean, still air, and quickly. The opposition of Mars in October 1894 would be the last good one for more than a decade.6

Mars and Earth are at their closest distance every 26 months when their orbits are in “opposition”, but some oppositions put them closer than others. The 1894 opposition was a close one, so it presented an especially good viewing opportunity.

Lowell immediately pivoted his career at age 38 to seek life on Mars. He quickly hired staff and asked them to find a location for his new observatory, which he built with his own funds. Lowell Observatory was founded in Flagstaff, Arizona where he believed the viewing would be best.

[H]e was returning to his passion. He had wrapped his imagination around [the] canals and became intent on reinventing himself as an astronomer. By the end of the decade, he had built his own observatory and convinced lay readers around the world that Martian engineers had built a canal system in order to save their dying world.7

Seeing is believing?

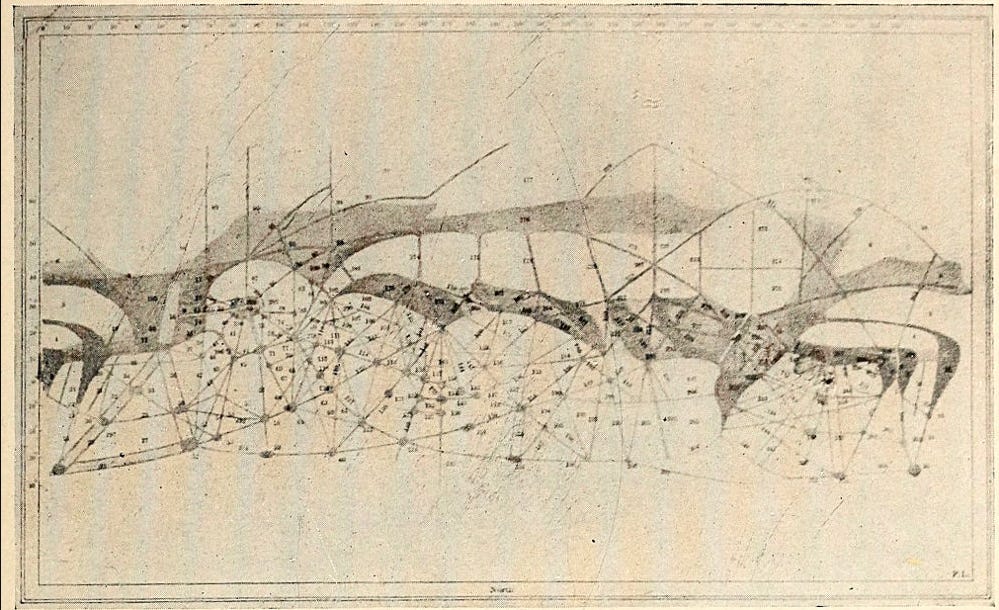

The NASA image8 on the left depicts what Mars actually looks like. The image on the right is a photo of a Martian globe9 that features Lowell’s planet-wide canal system. Lowell published many maps of the canals drawn in excruciating detail, like this one depicting a small section of the planet.10

At first Lowell’s maps and claims were received with interest among astronomers. But problems arose for Lowell as other astronomers, especially those with better telescopes, couldn’t see the canals.

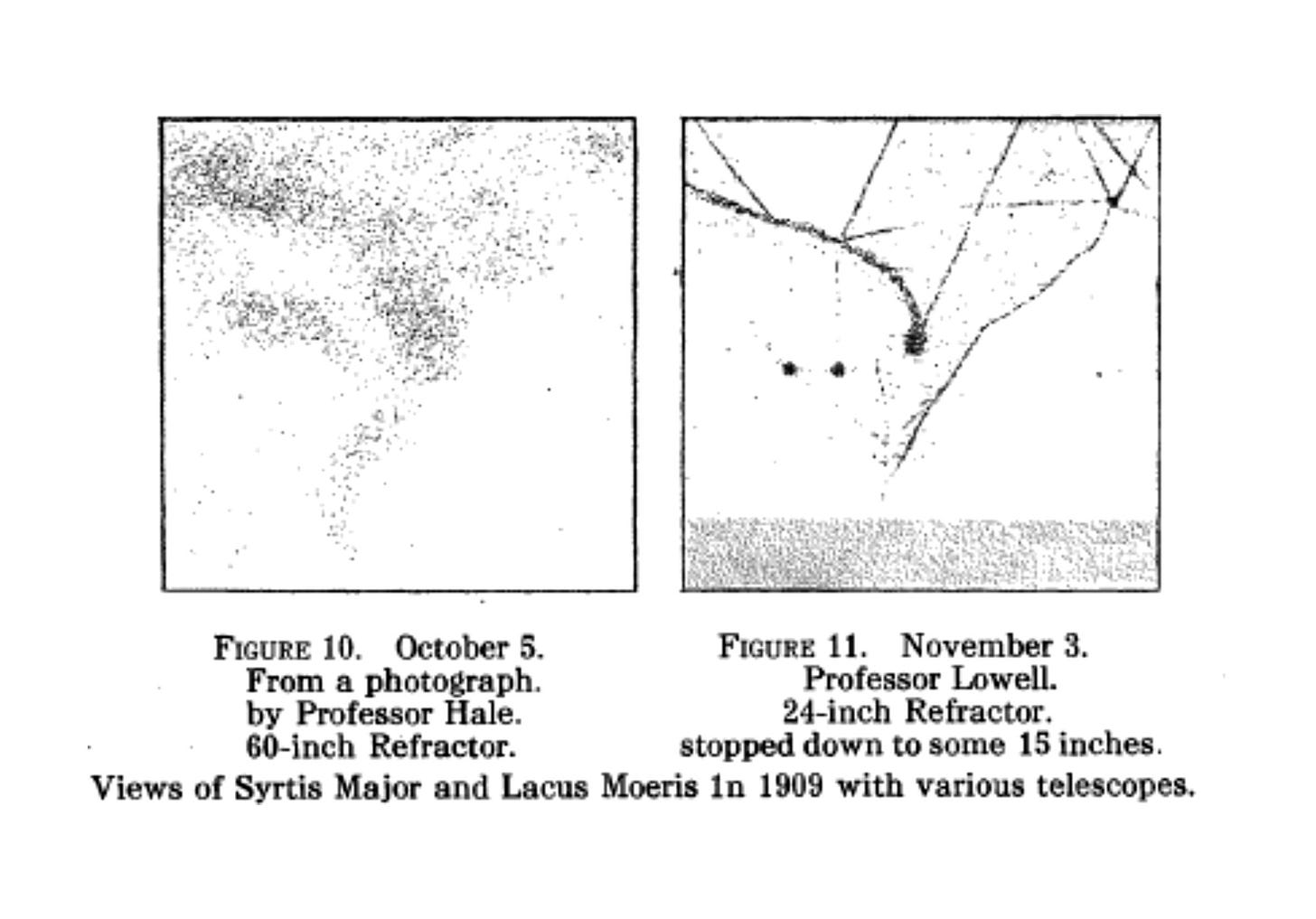

The following pair of images shows what Lowell claimed to see in his telescope’s eyepiece compared with what would be visible to a more objective observer using better equipment.11

The image on the left is a photograph taken in 1901 using the then-largest telescope in the world. The image on the right is a drawing by Lowell of the same location in the same year showing the lines that he perceived and interpreted as canals. When compared with the image from a much better telescope, some of Lowell’s lines can be seen to follow the outlines of darker shapes on the planet, while others (the straight lines) have no correspondence in the photograph, casting doubts on his maps.

The work of madmen

Mainstream astronomers began challenging Lowell’s credibility as early as 1896, only one year after he published the first of his three books on Mars. In that year, Lowell reported seeing surface markings not just on Mars, but on Venus, which is surrounded by a thick atmosphere with a flat, uniform, white appearance. In a recent book, astrophysicist David Weintraub writes:

No other astronomer could see the surface markings on Venus, and, to this day, no other astronomer has ever claimed to have seen the surface of Venus using a telescope on Earth….With the publication of his maps of Venus in December 1896, Lowell turned himself into a marked man among those whom he thought of as professional colleagues. They did not think of Lowell, who had no professional training or credentials as an astronomer, as a professional equal, and his studies of Venus turned him into a pariah among astronomers.12

One of Lowell’s early supporters, Eugène Michael Antoniadi, became one of his most vocal critics. In an 1898-1899 report, he wrote,

“It is hoped that the [report] will dispel the last doubts to the true character of the markings on the planet. The frail testimony of small [telescopes] has vanished before the decisive evidence of giant instruments; and the telescopes of Princeton, Lick, Yerkes, Mount Wilson, and Meudon have settled the question forever.”13

By 1907, “despite a spectacular publicity campaign by Lowell and his staff featuring photographs of the greatest canals, many of the early canalistas had recanted.”14

Additional criticism was voiced by Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection, who attacked Lowell’s canals on logical grounds. Why were the canals so straight? Wouldn’t they follow the planet’s topography? Also, why build more than 100,000 miles of canals to move the tiny amount of water believed to exist at the poles? He concluded, that the canals, “would be the work of a body of madmen rather than of intelligent beings”.15

Instead of retreating in the face of such criticism, Lowell doubled down on his claims.

In 1907 Lowell invested a sizable sum of money in taking photographs of the Martian Canals. In his opinion these images removed all doubt about the existence of canals on Mars. However, by opening up the interpretation of the observations behind the various maps of the planet the images ended up contributing to a loss of credibility in his work. The precise looking maps…carried a kind of weight, clarity and authority in justifying the idea of canals on Mars, but with photography came a new representation which made the seemingly objective maps of the previous era look deeply subjective. While the canals appeared obvious to…Lowell, the photographs were not convincing to others.16

By the time of his death in 1916, Lowell had lost the support of most scientists. As the New York Times put it in his obituary,

Professor Lowell was not in the least disturbed by the hostile judgments of his theories or their rejection by learned bodies. He kept bravely at his appointed task of studying Mars until the end of his life, and it is not to be doubted that the results of some of his observations will stand the test of time. The present judgment of the scientific world is that he was too largely governed in his researches by a vivid imagination.17

One hundred years later, in 2017, Lowell published an apology on Twitter (now X)18:

Oh wait…that was a parody account. Or was it?!

The “dead planet”

With his death, belief in Lowell’s canals began to fade. The last reported canal sightings were in 1924 and 193919. The matter was definitively settled on July 15, 1965 when NASA’s Mariner 4 spacecraft returned the first-ever close-up images of Mars.

Mariner’s grainy images revealed a cratered moonscape with no canals, cities, or vegetation. Two weeks later, in an editorial titled “The Dead Planet”, the New York Times declared:

Mars is probably a dead planet. The astronomers of past decades who thought they detected canals on the Martian surface and speculated that it might have bustling cities and beings engaged in lively commerce were victims of their own fantasies. So, too, were the science-fiction writers who made Mars a realm of epic battles and of weird but fascinating civilizations. The red planet is not only a planet without life now but probably always has been.20

The Times may have been premature in its 1965 pronouncement that Mars is a dead planet. Subsequent discoveries of methane and organic molecules, water on and below the surface of Mars, and possible bacterial fossils in a Martian meteorite found on Earth (still disputed 20 years later) have provided hope to those wishing to prove the existence of past or present life on Mars.

No definitive evidence for the presence of past or present life on Mars has yet been discovered. We are still waiting for that proof or for clear and strong evidence that says Mars is and has always been barren. But without any doubt, Mars was once hospitable to life; it was a planet on which Earthlike forms of life might have flourished.…[W]e absolutely cannot definitively deny that life might have existed and might still exist on Mars. We are still chasing Martians.21

The Wizard of Mars

Lowell’s theories had a major impact on both science and culture for much of the 20th century. For the most part, scientists seemed all too eager to forget about Lowell and his canals. However, one of his claims, that changes in the dark areas of Mars represented seasonal vegetation, was endorsed by many scientists right up until the Mariner 4 photos disproved that notion. Just two years before Mariner, a 1961 National Academy of Sciences report concluded that “these color changes can be attributed to the seasonal growth and decay of Martian vegetation.”22

In contrast, the idea of life on Mars was embraced enthusiastically within popular culture. Lowell’s work inspired books like Red Planet by Robert Heinlein (1949), The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury (1950), Arthur C. Clarke’s The Sands of Mars (1951), and Isaac Asimov’s The Martian Way (1952), to name just a few of the more famous entries. By my count, using IMDB’s database, there have been 68 sci-fi movies with the words “Mars” or “Martian” in their title, including “blockbusters” like Invaders from Mars (1953), The Wizard of Mars (1965), Mars Needs Women (1968), and Flight to Mars (1951) (which I actually watched as part of my research for this essay — you’re welcome!).

How could this happen?

How could Lowell have gotten things so wrong? How could his “vivid imagination” have allowed him to see and describe hundreds of canals when there were none? How could he have let himself get carried away with speculation, especially in the face of intense criticism from renowned astronomers who had better training and better telescopes? Here are some of the factors at play.

Lowell was biased from the start

Lowell’s two-decades-long Mars observing campaign confirmed in his own mind his hypothesis, of which he was certain of the answer before he even began his study: Mars was inhabited by an intellectually advanced civilization.23

Calling this a “hypothesis” may overstate Lowell’s objectivity in the matter.

The nature of Lowell’s quest is revealed by what he said and wrote of the canals in the months before he first trained his new telescopes on Mars. Writing in the Boston Commonwealth on 26 May 1894, Lowell said: “The most self-evident explanation from the markings themselves is probably the true one; namely, that in them we are looking upon the result of the work of some sort of intelligent beings”24

He was hampered by a lack of scientific training

Although Lowell studied mathematics and astronomy at Harvard, he was not trained as a scientist. Recall that as a wealthy man, he was able to build his own observatory, make his observations, and publicize his results without being hired or vetted on the basis of his competence or qualifications. He had money, he called himself an astronomer, and the public believed him.

One of his assistants, Andrew E. Douglass, whom Lowell fired for “untrustworthiness” after he expressed doubts about the canals on Mars and the markings on Venus, criticized Lowell’s approach. Douglas stated that Lowell’s “method is not the scientific method and much of what he has written has done him harm rather than good….I fear it will not be possible to turn him into a scientific man.”25

The evidence was “fuzzy”

Lowell’s relatively small telescopes yielded blurry, unstable images of Mars which were ambiguous and open to interpretation.

The uncertainty about the canals was possible because the features of Mars—like those of other planets—are grossly blurred when seen through the earth's turbulent atmosphere. Looking at them is like looking at the bottom of a stream through running water. A photograph of the bottom produces a meaningless, distorted image, yet a viewer can draw a picture of the bottom that is fairly accurate by piecing together patches of the scene that come into sharp focus at different times. However, his expectations play an important role in this process. He expects to see rocks and pebbles on the bottom. Lowell expected to see canals and so he saw them. This psychological phenomenon has probably played a tole in many of the flying-saucer episodes. It has also led careful and sober scientists astray in their laboratory studies.26

Matthew J. Sharps, a forensic psychologist who specializes in eyewitness phenomena, visited the Lowell Observatory in 2018 to research how Lowell “saw” the nonexistent canals. He reported what the untrained eye sees when viewing Mars through the same telescope that Lowell used:

Now, I am an aging researcher with very thick glasses, but what I can say is that the observations danced before me very swiftly, the result of atmospheric fluctuation. Sometimes I would seem to see a feature on Mars, and then it was gone, or obscured, within two or three seconds. This type of highly variable, atmospherically based visual fluctuation would certainly have been there for Lowell and his colleagues as well.27

Lowell was defensive in the face of criticism

Early on in his Mars research, Lowell blamed his critics for their lack of skill. “The fact that he…could see Martian structures that others could not see was, he believed, simply a physical failing on the parts of others.”28 Later, in the years before his death, he attacked them more personally, stating in a 1915 lecture:

The objections arise only from those who have never properly observed the planet, or who quote others in the like predicament. It is a case of science versus nescience [a lack of knowledge or awareness, or ignorance].29

Thus, he attacked his critics rather than considering evidence that contradicted his claims. This was especially egregious since the contradictory evidence came from observations that were made using much better telescopes.

Insects on Mars

In summing up Lowell’s life, the New York Times’ obituary concluded, “He was not a poser or a ‘sensationalist,’ he did nothing for notoriety's sake.” None of the sources I reviewed accused him of deliberate fabrication or of doing it for the money (as noted previously, he was already wealthy). So why was he so blind to his errors?

Lowell’s biographer put it this way:

Lowell himself was convinced that his own brilliance made it difficult for less intelligent men to recognize his work. This rationalization served to blind him to the fact that much of the opposition to his work was generated by his own failure to employ recognized scientific methods or to acknowledge changing norms in the disciplines.30

Lowell believed from the start that canals existed on Mars, and when viewing the fuzzy, wavering images of the planet through his telescopes, he saw them. The images Lowell viewed through his telescope were like a Rorschach ink blot upon which he could project his fantasies. His stubbornness and lack of training enabled him to dismiss his critics, believing that only he and those who agreed with him could perceive the truth.

Confirmation bias such as this can interfere with objective interpretation of any form of data, be it telescopic images of Mars or the latest political polls. The more ambiguous or “fuzzy” the data and the more we are invested, emotionally or intellectually, in the results, the more we need to take a step back and question our assumptions and interpretations. Sometimes it helps to listen to critics with an open mind. A little bit of humility goes a long way. Unfortunately, humility was a quality that was not abundant in Lowell’s personality.

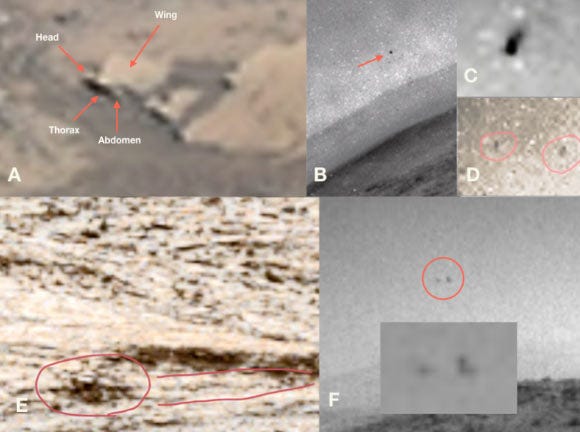

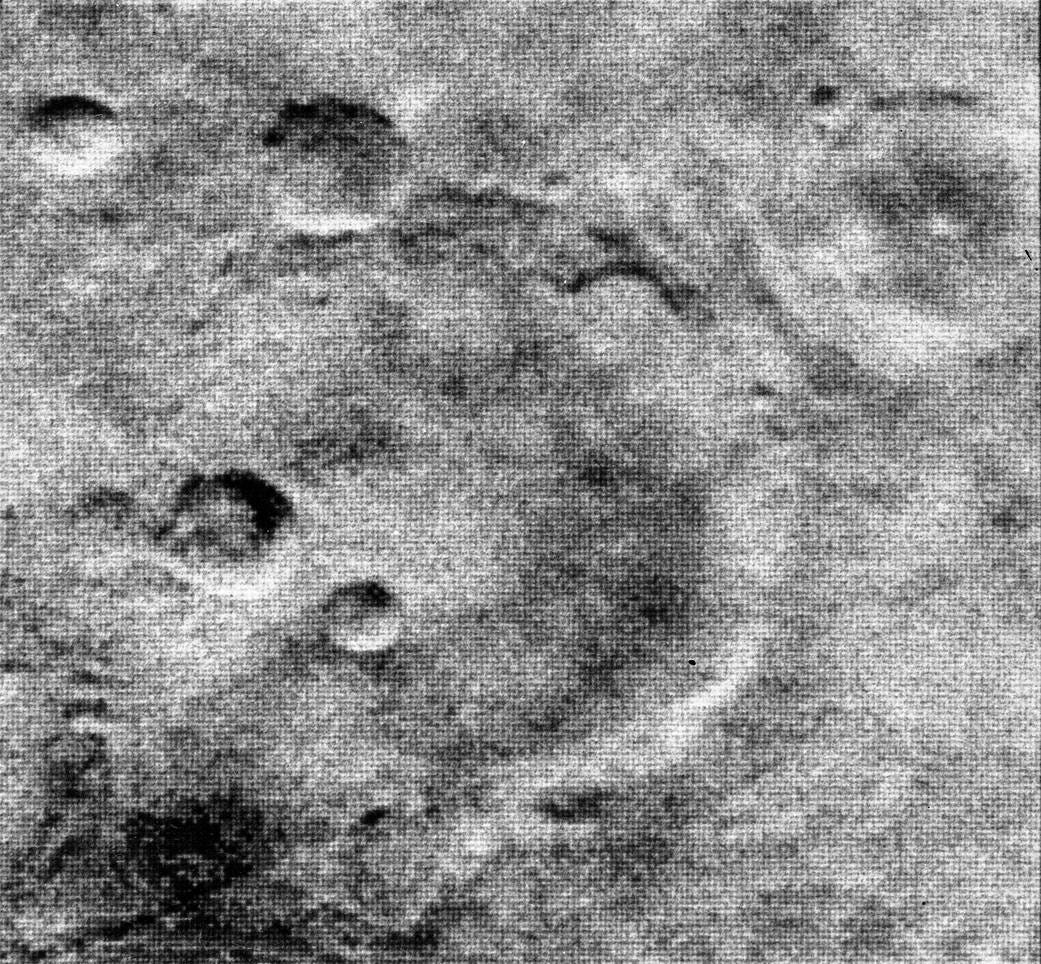

Confirmation bias continues to taint science and other endeavors to this day. In 2019, an Ohio University entomology professor, William Romoser, made an extraordinary claim, announcing that his perusal of images from NASA’s rovers revealed insect-like life forms on Mars.

There has been and still is life on Mars…There is apparent diversity among the Martian insect-like fauna which display many features similar to terran insects that are interpreted as advanced groups — for example, the presence of wings, wing flexion, agile gliding/flight, and variously structured leg elements.31

Here are some of the images he identified.

With this discovery in mind, I’ll close this essay with a second quiz: if astronauts ever land on Mars, should they carry bug spray?

This is an AI image I created using Microsoft designer with the prompt, “An image of Mars with the canals reported by Percival Lowell around 1900. A landscape with mountains and futuristic buildings in the background and canals in the foreground. A Martian as imagined in the early 1900s is in the foreground. Styled as an illustration from 1910.”

https://www.loc.gov/collections/finding-our-place-in-the-cosmos-with-carl-sagan/articles-and-essays/life-on-other-worlds/seeing-and-interpreting-martian-oceans-and-canals

https://www.nature.com/articles/35084148

https://www.loc.gov/collections/finding-our-place-in-the-cosmos-with-carl-sagan/articles-and-essays/life-on-other-worlds/seeing-and-interpreting-martian-oceans-and-canals

https://www.nature.com/articles/35084148

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/press_kits/mars_2020/launch/mission/science/

https://societyforthehistoryofastronomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/shanewsletter08.pdf

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47015/47015-h/47015-h.htm

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

https://www.nature.com/articles/35084148

https://www.nature.com/articles/35084148

https://www.loc.gov/collections/finding-our-place-in-the-cosmos-with-carl-sagan/articles-and-essays/life-on-other-worlds/seeing-and-interpreting-martian-oceans-and-canals

New York Times, "Percival Lowell" obituary, November 14, 1916

https://x.com/percivallowell4/status/824655986665394178?s=61

https://www.nature.com/articles/35084148

NYT editorial "The Dead Planet", July 30, 1965

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1971ARA%26A...9..147I

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

https://www.nature.com/articles/35084148

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

NYT "Mars-Tantalizing Questiion Mark", July 11, 1965

https://skepticalinquirer.org/2018/05/percival-lowell-and-the-canals-of-mars/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc774fn

NYT, "New Light on Mars Canals", December 1, 1915

https://openlibrary.org/works/OL6694960W/Percival_Lowell?edition=key%3A/books/OL7670369M

https://www.sci.news/space/insect-reptile-like-life-forms-mars-07830.html

I was about to comment on the similarities between Lowell and Trump, but France beat me to it! A well crafted response to David’s well researched article.

You have outdone yourself with this one, Dr. Dave! By the way, Brody has started his first year at NM Tech studying astrophysics. He intends to be on a NASA mission to Mars someday. That kid has demonstrated enduring focus many times in his 18 years. I have no doubts about his ability to achieve his goals.